.jpg)

Giovanni Martinelli is for me the greatest tenor of the recorded era: what I wouldn’t give to have heard live, his performances of Otello or Il Trovatore. Luckily he was quite well recorded, albeit not always in the best quality (his best recordings were made between about 1915 and 1941 so that is not so surprising), but they do none-the-less capture the excitement and quality of the voice. A short biography of Martinelli can be found below, whilst reviews and opinions can be found here, Reviews.

For this biography I quote extensively from the book accompanying a 3 LP set of Martinelli that I was lucky enough to purchase in a second hand LP shop in New York titled 'Giovanni Martinelli: In Memoria'. The article in the boxed set is called, 'Giovanni Martinelli, The Last of the Titans', and is written by Edward J. Smith.

I remember my first encounter with Martinelli: I had become fascinated with Verdi's Otello, particularly as my favourite tenor at that time, Jussi Bjorling, did not record the complete opera and the great tenor Caruso also died before recording or performing it. The sleeve notes on one of Bjorling's LPs, where he thrillingly sang two arias from the opera, mentioned Martinelli, so one day while looking through the HMV classical department whilst on a trip to London, I noticed a complete recording by him of the Opera. The sleeve of the CD did not promise much, but I duly purchased the twin CD set and as soon as I returned home that night, started playing it. The quality was not good and Martinelli's entrance in the Esultate did not immediately thrill. But slowly, he entranced, surprised, enraptured me. On more and more playings more and more layers to the performance were found. Without doubt I was listening to the greatest Otello since Tamagno or to quote John Steane, '....a performance of unsurpassed intensity unequalled (I think) in its power to impress itself upon the memory and imagination.'

'The afternoon of November 17, 1917

saw a performance of Faust presented at the Metropolitan Opera House

in New York. Performers included Geraldine Farrar as

Marguerite, Leon Rothier as Mephistofoles and Giovanni

Martinelli in the title role [A photograph of Martinelli  as

Faust from 1918 is shown on the right]. That evening a party was held

in the home of a director of the company for the artists and various

guests. Present was a small boy, age four years. As the adults enjoyed

themselves the boy squeezed himself into a corner and tried to stay

out of the way. Seated at the piano idly fingering the keys was the

hero of the afternoon's presentation, Giovanni Martinelli. He noticed

the boy and beckoned him to approach. 'Are you frightened', asked the

tenor? The boy nodded shyly. 'Shall I sing to you?' inquired the tenor.

Again the child nodded his head. Martinelli reached down and swept

the boy into his arms. He seated him on his left knee and with his

right hand sought the proper notes of accompaniment on the piano....'

Mi batte il cor - spettacol divin - sognata terra - ecco ti premo alfin

- the recitative before the great solo, O Paradiso from Africana, came

pianissimo and then stronger from the throat of the tenor. The voice

swelled as the tenor warmed to his task, while the child, at first

comforted, grew alarmed as the clarion voice rang throughout the room

- Then it happened. Forgetting the boy on his knee the tenor opened

up with the phrases on Tu m'appartiene from G to B flat crescendo -

and his voice rang like a trumpet ... The frightened child slipped

crying from his lap, slapt his face hard, and ran to his corner to

hide, his eardrums bursting from the noise the tenor's stentorian organ

had created. This was Edward J. Smith's first association with Giovanni

Martinelli, an association which continued for 52 years until the great

tenor left this world to join his comrades in the opera companies of

heaven.' [A photograph of Martinelli with Edward J Smith is shown on

the below]

as

Faust from 1918 is shown on the right]. That evening a party was held

in the home of a director of the company for the artists and various

guests. Present was a small boy, age four years. As the adults enjoyed

themselves the boy squeezed himself into a corner and tried to stay

out of the way. Seated at the piano idly fingering the keys was the

hero of the afternoon's presentation, Giovanni Martinelli. He noticed

the boy and beckoned him to approach. 'Are you frightened', asked the

tenor? The boy nodded shyly. 'Shall I sing to you?' inquired the tenor.

Again the child nodded his head. Martinelli reached down and swept

the boy into his arms. He seated him on his left knee and with his

right hand sought the proper notes of accompaniment on the piano....'

Mi batte il cor - spettacol divin - sognata terra - ecco ti premo alfin

- the recitative before the great solo, O Paradiso from Africana, came

pianissimo and then stronger from the throat of the tenor. The voice

swelled as the tenor warmed to his task, while the child, at first

comforted, grew alarmed as the clarion voice rang throughout the room

- Then it happened. Forgetting the boy on his knee the tenor opened

up with the phrases on Tu m'appartiene from G to B flat crescendo -

and his voice rang like a trumpet ... The frightened child slipped

crying from his lap, slapt his face hard, and ran to his corner to

hide, his eardrums bursting from the noise the tenor's stentorian organ

had created. This was Edward J. Smith's first association with Giovanni

Martinelli, an association which continued for 52 years until the great

tenor left this world to join his comrades in the opera companies of

heaven.' [A photograph of Martinelli with Edward J Smith is shown on

the below]

'The story of Martinelli's youth

is well known but it does bear some repetition. He was born in the

city of Montagnana, Italy, October 22, 1885, son of a cabinet maker.

[There seems to be some dispute over this date: the Music and Arts

CD of the 1938 Otello gives 1883 as his birth date whereas the comment

in the Pearl 1941 CD states, 'Martinelli was 56 (or even older if the

date of his birth given in most books is now deemed incorrect]'. At

the age of six, when he had developed a fine soprano voice, the future

star was taken by an aunt to the local church. Here the priest was

sufficiently impressed to use the child to sing solos in the choir

and to pay him one lire a month for four such solos. On Wednesday,

January 29th, the evening before he was stricken with a ruptured aorta,

Giovanni Martinelli sang portions of Otello in his apartment, while

giving a vocal lesson to a pupil. This tenor, brokenly, told later

on, that if he could at any time imitate the sounds of Giovanni Martienlli

on that last day, he would be the happiest mortal alive. So the unbroken

singing chain continued for more than 77 years without let up. In his

early days, since the  family

was a large one, Martinelli worked in the fields picking grapes and

also as a blacksmith, shoeing horses and working with iron and steel

in the making of carriage wheels. Much of the furniture in his own

home was designed by him, and he would proudly state that had he not

only been but was an excellent cabinet maker.'

family

was a large one, Martinelli worked in the fields picking grapes and

also as a blacksmith, shoeing horses and working with iron and steel

in the making of carriage wheels. Much of the furniture in his own

home was designed by him, and he would proudly state that had he not

only been but was an excellent cabinet maker.'

'When Giovanni was twenty he was called upon to enter the Italian Army. At fourteen his soprano voice had broken but by 17 he had a natural tenor easily produced, and able to encompass a solid B flat without difficulty. In talking of these days, the tenor told me, "I could probably have sung higher, but it never occured to me to do so. I knew the popular songs of the day and I also sang such arias as Cielo e Mar from Gioconda and Celeste Aida without difficulty. I did not attempt to go above the B Flat." When he was 15 Martinelli had gone to Turin with his father and had heard a performance of Aida with Francesco Tamagno, then a bit past 50, as Radames [A photograph of Tamagno is shown on the right, in Messaline]. The young man was mightily impressed by the thunderous tones of the greatest dramatic tenor of the 19th century, and then was made even more aware of what great singing constituted when he visited Venice and heard Fernando de Lucia in aperformance of Barbiere di Siviglia with Mattia Bastistini. This was in 1903, and other than performances of opera in his own town of Montagnana he heard no more great opera.'

'In 1906, while in the barracks,

he set up a horn in the window and standing back of the horn he proceeded

to sing. This impromptu recital drew the attention of his bandmaster

who took him to the commanding officer of the Regiment. It was decided

that his talent was sufficient to escuse him from field work with the

army and he was appointed regimental cook. In the fall his captain

took him to Milano where he auditioned successfully and was offered

a scholarship. As Martinelli told the story, it was his singing of

the aria Dai campi dai prati from Mefistofele which decided the voice

was already perfectly placed and a debut was envisioned soon. Disaster

struck, when Martinelli was unable to get along with the instruction

given him and at the  end

of six months, he was off pitch, forcing terribly, unable to reach

his high notes, and cracking on these when by sheer physical force

he did get there. The sponsors, who owned a series of theatres akin

to the Schuberts in the U.S., decided to dismiss the youngster. Help

from a former tenor Giuseppe Mandolini and a young

conductor, Tullio Serafin, saved the day. Mandolini

demanded that Martinelli be put in his hands for training, and Serafin,

a rising young conductor, also pleaded for the dispairing youngster.

The sponsors relented and Martinelli moved into Mandolini's home to

study. This consisted of three hours of vocal work daily - an hour

in the morning - one in the afternoon and one in the early evening.

In between Martinelli studied music and opera scores and attended performances

at La Scala or the Teatro del Verme at night.At the end of six months

he was ready. A second audition followed and it was decided a debut

was in order.' [A photograph of Martinelli from 1913 is shown left]

end

of six months, he was off pitch, forcing terribly, unable to reach

his high notes, and cracking on these when by sheer physical force

he did get there. The sponsors, who owned a series of theatres akin

to the Schuberts in the U.S., decided to dismiss the youngster. Help

from a former tenor Giuseppe Mandolini and a young

conductor, Tullio Serafin, saved the day. Mandolini

demanded that Martinelli be put in his hands for training, and Serafin,

a rising young conductor, also pleaded for the dispairing youngster.

The sponsors relented and Martinelli moved into Mandolini's home to

study. This consisted of three hours of vocal work daily - an hour

in the morning - one in the afternoon and one in the early evening.

In between Martinelli studied music and opera scores and attended performances

at La Scala or the Teatro del Verme at night.At the end of six months

he was ready. A second audition followed and it was decided a debut

was in order.' [A photograph of Martinelli from 1913 is shown left]

'Martinelli had to give 20% of his earnings to these sponsors for a score of years and this sum eventually won for these people a sum of money close to $1,000,000. Two years prior to this, and before he had actually started his studies, the city of Montagnana put on a dozen performances of Aida in the months of September and October, 1908. The Radames was Giovanni Vals, a 36 year old tenor and one of the fine artists in Italy. Martinelli was asked if he would want to sing the Messenger in the performances. Eagerly he accepted and sang all 12 performances, receiving three lire a performance (60 cents). But for that enormous sum he also had to sing in the chorus when his part of the messenger was finished. "One did not earn three lire easily in those days," the Maestro would relate. Vals was impressed with the young man and told him, "Continue as you are going and in three years you will be singing Radames".

The first real public appearance

by Martinelli was at a performance of Rossini's Stabat Mater on December

3rd, 1910. His colleagues included Vittorio Arimondi, Virginia

Guerrini and Celestina Boninsegna. Martinelli

says that from a superstitious standpoint, he felt very good about

the presence of Boninsegna, not only because she was the foremost Italian

dramatic soprano of the day, but because of her name. Split the name

in two - Bonin - and - segna - meaning good sign. A good sign it was

for the young tenor received excellent notices, especially for the

sustained high D-flat in the Cujis Aninam.  On

December 29, 1910, the official debut in opera came with a performance

of Ernani. Mandolini was in the prompter's box, and as Martinelli recalled

the vent all he could remember was Mandolini's distorted face screaming

at him, "You idiot - you are forgetting again - I will kill you!" -

Musically it may not have gone so well, but the solidity of the voice

and the brilliance of the upper register brought the audience to its

feet and success was insured.

On

December 29, 1910, the official debut in opera came with a performance

of Ernani. Mandolini was in the prompter's box, and as Martinelli recalled

the vent all he could remember was Mandolini's distorted face screaming

at him, "You idiot - you are forgetting again - I will kill you!" -

Musically it may not have gone so well, but the solidity of the voice

and the brilliance of the upper register brought the audience to its

feet and success was insured.

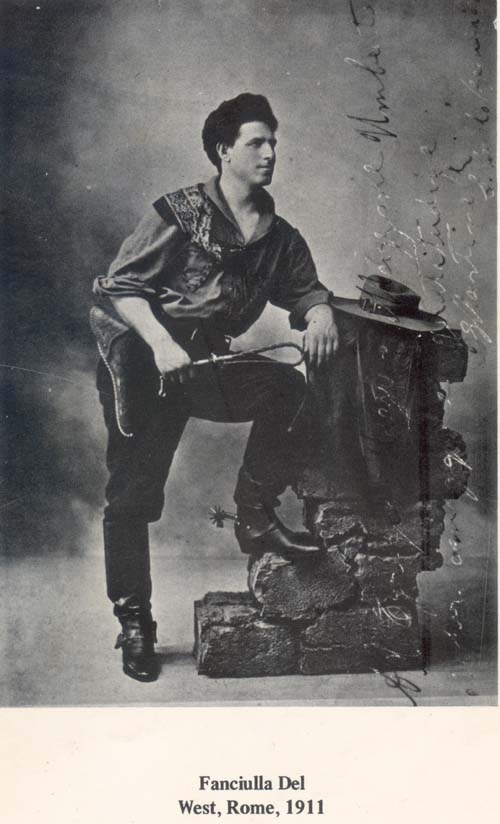

Following the Ernani success, the young man was engaged in Ancona, Brescia, Genoa and Turin. On his return from singing Ballo in Maschera in that city, his sponsors told him he was to sing an audition for Casa Ricordi, the most powerful of all European publishing houses. The tenor entered upon the stage of a darkened auditorium. Out of the depths a voice demended, "What will you sing for us?" Giovanni started with his two warhorses - Cielo e mar and Celeste Aida and finished with E lucevan le stelle from Tosca. The lights went on and three men climbed upon the stage. The first was Guilio Ricordi - but when Martinelli saw the other two his knees buckled, and he had to hold to the piano for support. "All the world knew these two," he related, "The first was Arturo Toscanini and the second was Giacomo Puccini. Toscanini kept stroking his moustaches. "Yes," he muttered, "He will do," "He will do very well," echoed Puccini. "Alright young man. We will take you." - Take me? "Take me for what?" pleaded the stunned young tenor. The composer and conductor laughed. Then he was told. Puccini's latest opera, Fanciulla del West, had premiered two months ago at the Metropolitan Opera House with Enrico Caruso. Now the Roma permiere - also the European premiere was to be given. Amedo Bassi had been engaged to take Caruso's place but Bassi had engagements at Covent Garden. He could sing but one performance. Another tenor was needed when Bassi departed. That tenor was to be Giovanni Martinelli.

Martinelli set to work at once - but the then strange harmonies of Puccini with the almost tonal school and musical jumps so different from the bel canto school in which he had been trained puzzled the singer. After a month of study he was called upon to sing an audition for Toscanini. The great conductor listened with growing impatience - "No, No, No!" he shouted, "You will not do. You are too much of a recruit for me. I must have someone who knows - No - go back home ..." The heart of Martinelli sank in his chest. Summoning a smile, he replied wanly, "Si Maestro..you are right...I am not ready..but at least I go home with two great things accomplished." "What is that?" demanded Toscanini. "I have been to Roma, and I have had an hours work with Arturo Toscanini ." The maestro's scowl vanished and a smile creased his face. "Martinelli, you are a 'sympatico giovine'", he declared. "We will work together. You are not the idiot I suspected." Soon under Toscanini's direction, the musically trained Martinelli grasped what was wanted and after the first performance he replaced Bassi in the world premiere performances of Fancuilla. "Toscanini even allowed me a bis after Ch'ella mi creda", Martinelli told with immense pride. With his compatriots Eugenia Burzio and Pasquale Amato, the young man made musical history at the Costanzi Theatre. All of Europe's most famous maestri were at the performances - and Martinelli was heard not just by famous conductors but equally famous theatre directors. Engagements in Monte Carlo, Brussels and Budapest followed.

Cleofonte

Campanini, director of the opera at Covent Garden, also heard him,

and in the spring of 1912, Giovanni Martinelli, age 27, set out for

London. His debut took place April 22, 1912 in Tosca, and Herman Klein,

foremost of the living British critics declared, "He has that

rare gift - a true tenor voice. It remains the finest tenor heard in

England for years. Its quality is luscious, ringing, musical and delightful

to hear. The moment he had finished Recondita armonia, the house rose

at him." All in all, over five seasons - 1912, 1913, 1914, 1919

and 1937, Martinelli sang over 90 performances of fifteen operas at

Covent Garden. These included Aida, Fanciulla del West, Gioelli della

Madonna, Manot Lescaut, Tosca, Dubarry, Butterfly, Pagliacci, Ballo

in Maschera, Boheme, Francesca da Rimini, Faust, Carmen, Turandot and

Otello.

Cleofonte

Campanini, director of the opera at Covent Garden, also heard him,

and in the spring of 1912, Giovanni Martinelli, age 27, set out for

London. His debut took place April 22, 1912 in Tosca, and Herman Klein,

foremost of the living British critics declared, "He has that

rare gift - a true tenor voice. It remains the finest tenor heard in

England for years. Its quality is luscious, ringing, musical and delightful

to hear. The moment he had finished Recondita armonia, the house rose

at him." All in all, over five seasons - 1912, 1913, 1914, 1919

and 1937, Martinelli sang over 90 performances of fifteen operas at

Covent Garden. These included Aida, Fanciulla del West, Gioelli della

Madonna, Manot Lescaut, Tosca, Dubarry, Butterfly, Pagliacci, Ballo

in Maschera, Boheme, Francesca da Rimini, Faust, Carmen, Turandot and

Otello.

After Covent Garden in 1912, Martinelli returned to Italy where he created Marzio in Zandonai's Melenis in Milano and followed this with his La Scala debut in Fanciulla with Galeffi and Poli-Randaccio. Prior to this he had sung over 20 performances of Manot Lescaut at the Dal Verme in Milano with Claudia Muzio.

When time came to put on the Fanciulla, La Scala intended to engage Bernardo de Muro (shown left), a splendid dramatic tenor, four years Martinelli’s senior. The management did not want a young man who had been singing at a rival but lesser theatre. Puccini put a stop to this. He wired the La Scala management. “Martinelli sings Johnson or you do not do Fanciulla”. Martinelli sang Johnson. Martinelli recalled at this time being present in Puccini’s suite when Toscanini was making suggestions for certain musical changes he felt would help the opera. Puccini, lying on his back on the bed, listened with growing irritation. “Basta”, he said, “If the Girl was born with Gambi storti”, lascia cosi…”If Fanciulla was born with twisted legs, it’s too bad. Leave her alone”. Toscanini argued no more. On August 7 th, 1913, the up and coming young tenor married Adele Prevatali of Roma. This marriage which produced three children passed its 55th anniversary in August 1968.

Following

the recommendations of Toscanini and Clefonte Campanini who was conducting

the Philadephia-Chicago Company, Giulio Gatti-Casazza engaged Martinelli

for the Metropolitan for the fall of 1913. The young tenor arrived

by boat with his young bride in late October. Not knowing what to expect,

Gatti ‘loaned’ Martinelli to the Philadephia-Chicago Company

for its opening performance of Tosca in Philadephia. Martinelli sang

with Mary Garden and Vanni-Marcoux as

Scarpia. Garden sang the opera in a mixture of Italian and French – but

mostly in French. Listening in the wings, Martinelli was astounded

to hear Garden snarl out the words – “E avanti a lui, tremava

tutta Roma”, and then dropping a crucifix on Scarpia’s

chest, she turned to the audience and declared “Viola, C’est

fait”… and then made her exit.

Following

the recommendations of Toscanini and Clefonte Campanini who was conducting

the Philadephia-Chicago Company, Giulio Gatti-Casazza engaged Martinelli

for the Metropolitan for the fall of 1913. The young tenor arrived

by boat with his young bride in late October. Not knowing what to expect,

Gatti ‘loaned’ Martinelli to the Philadephia-Chicago Company

for its opening performance of Tosca in Philadephia. Martinelli sang

with Mary Garden and Vanni-Marcoux as

Scarpia. Garden sang the opera in a mixture of Italian and French – but

mostly in French. Listening in the wings, Martinelli was astounded

to hear Garden snarl out the words – “E avanti a lui, tremava

tutta Roma”, and then dropping a crucifix on Scarpia’s

chest, she turned to the audience and declared “Viola, C’est

fait”… and then made her exit.

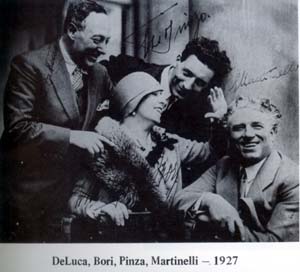

On November 20 th, 1913, with Antonio Scotti and Lucrezia Bori in his cast, Giovanni Martinelli sang the first of 26 Bohemes he was to sing at the Metropoltan. He was recognised immediately as one of the finest tenors to have joined the Metropolitan since Caruso and within the first season, he as declared by Caruso to be his ‘Crown Prince’. Martinelli had sung with Caruso at Covent Garden and he worshipped his older colleague.

Only once did this writer ever see Martinelli really angry. At a party an overdressed flamboyant woman persisted in demanding answers to questions in a loud voice to attract attention. Finally she said, “Come now, Mr. Martinelli, tell us the truth – Caruso was never as good as hiss press made him to be, is that not the truth.” Martinelli swung around and faced his tormentor. “Madame”, he declared in his accented but thoroughly accurate English, “Put Gigli, Lauri-Volpi and me together – make us one tenor – and we would not be fit to kiss Caruso’s shoe tops”. “Does that answer you?”

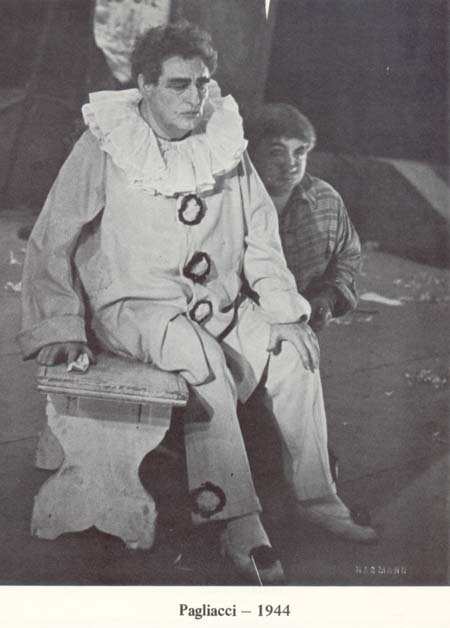

After

having heard a performance of Pagliacci with Caruso in 1913, Martinelli

decided he needed much more before he could compete. He went to Ruggero

Leoncavallo, composer of Pagliacci and asked his help. “Are

you crazy”, demanded the composer. “You ask me to help

you when you have the Canio of my dreams singing with you at the Metropolitan.

Go to Caruso – he can help you – not I.” Martinelli

was still too shy to ask, but Leoncavallo wrote Caruso who immediately

invited – nay – demanded that his young colleague attend

his rehearsals and come to his performances. After one Pagliacci in

1913, Caruso asked Giovanni who had come backstage at the end, “Giovanni,

did you like my Canio tonight?” Martinelli stammered that he

was still hypnotised by the power and dramatic utterances of Caruso – it

was incomparable, he said, “Caruso looked at him – “You

know”, he said, “I do not care for the way you have been

costuming Canio.” He turned to his valet, “Give Giovanni

one of my costumes. This is authentic commedia del arte, Giovanni,” he

said. “Wear it in your next performance.”

After

having heard a performance of Pagliacci with Caruso in 1913, Martinelli

decided he needed much more before he could compete. He went to Ruggero

Leoncavallo, composer of Pagliacci and asked his help. “Are

you crazy”, demanded the composer. “You ask me to help

you when you have the Canio of my dreams singing with you at the Metropolitan.

Go to Caruso – he can help you – not I.” Martinelli

was still too shy to ask, but Leoncavallo wrote Caruso who immediately

invited – nay – demanded that his young colleague attend

his rehearsals and come to his performances. After one Pagliacci in

1913, Caruso asked Giovanni who had come backstage at the end, “Giovanni,

did you like my Canio tonight?” Martinelli stammered that he

was still hypnotised by the power and dramatic utterances of Caruso – it

was incomparable, he said, “Caruso looked at him – “You

know”, he said, “I do not care for the way you have been

costuming Canio.” He turned to his valet, “Give Giovanni

one of my costumes. This is authentic commedia del arte, Giovanni,” he

said. “Wear it in your next performance.”

The costume is preserved in the Martinelli home. It has never been worn. “I could not desecrate it by wearing it, “Martinelli explained simply.

In 1916, then recognised as second only to Caruso among the tenors of the world, Martinelli went to Beunos Aires to sing. He appeared in Boheme, Aida, Faust, Tosca, Ballo in Maschera, Trovatore and Hugenots. Following this first performance of the Meyerbeer opera he returned to his dressing room and found a distinguished looking old man waiting to see him. In excellent French-accented-Italian this man escused himself, and then said, “Young man, you sang magnificently. But here were certain things you did in the duet finale ‘Dillo ancor’ in Italian, which I do not think were right. May I show you the proper phrasing?” “Of course,” replied Martinelli. The man seated himself at the dressing room piano and proceeded to demonstrate. “I was a pupil at the Paris Conservatoire when Meyerbeer used these phrases to illustrate certain legato effects, “he said. “He wanted them done this way – .” Martinelli was amazed and tried the attacks to the high C flats as directed. They came out much easier and flowed instead of being difficult to attack. The tenor proceeded to thank his coach profusely and the man started to leave. “But what is your name,” demanded Martinelli, “The old man smiled, “Camille Saint Saens,” he said.

Also

in 1916, Martinelli met and sang for Arrigo Boito.

He asked the veteran composer’s help in studying Otello, for

which Boito had written the libretto. Back of Martinelli’s mind

was the thought that someday he too might sing the opera. He had been

fascinated with it ever since he heard Franz sing

it Covent Garden and Zanatello in Boston. Boito was

much taken with the Martinelli voice. “I am almost finished with

an opera I have worked on for forty years,” he told Martinelli. “When

it is finished it will be done at La Scala. I would like you to create

it. It is called Nerone.” Boito died at 76 in 1918 and the war

and Italy’s recovery prevented the launching of Nerone until

1924. Then Martinelli was singing in America. Toscanini, then director

of La Scala, summoned him to Milano to create the part as had been

requested by Boito. But Toscanini and Gatti-Casazza were fueding – and

hated each other. “Go, my friend,” Gatti told Martinelli, “But

if you sing for Toscanini you will never sing again at the Metropolitan.” Martinelli’s

first two children had been born in New York and were going to school

there – his whole life revolved around the Metropolitan. So,

he reluctantly declined the invitation. Aureliano Pertile,

his colleague and fellow tenor from Montagnana sang the premiere of

Nerone…

Also

in 1916, Martinelli met and sang for Arrigo Boito.

He asked the veteran composer’s help in studying Otello, for

which Boito had written the libretto. Back of Martinelli’s mind

was the thought that someday he too might sing the opera. He had been

fascinated with it ever since he heard Franz sing

it Covent Garden and Zanatello in Boston. Boito was

much taken with the Martinelli voice. “I am almost finished with

an opera I have worked on for forty years,” he told Martinelli. “When

it is finished it will be done at La Scala. I would like you to create

it. It is called Nerone.” Boito died at 76 in 1918 and the war

and Italy’s recovery prevented the launching of Nerone until

1924. Then Martinelli was singing in America. Toscanini, then director

of La Scala, summoned him to Milano to create the part as had been

requested by Boito. But Toscanini and Gatti-Casazza were fueding – and

hated each other. “Go, my friend,” Gatti told Martinelli, “But

if you sing for Toscanini you will never sing again at the Metropolitan.” Martinelli’s

first two children had been born in New York and were going to school

there – his whole life revolved around the Metropolitan. So,

he reluctantly declined the invitation. Aureliano Pertile,

his colleague and fellow tenor from Montagnana sang the premiere of

Nerone…

In late 1921, Martinelli visited Puccini at the composer’s home at Torre del Lago. Puccini was working on his final opera, Turandot. He called Martinelli into the music room. “Sing this, Giovanni”, he said and handed the tenor a piece of manuscript music he had just finished. Martinelli picked it up, and reading at sight began, ‘Nessun Dorma’ – When he finished Puccini demanded an encore in full voice. Highly pleased the composer said, “The opera should be ready by 1923 and I want you for my Calaf. I will tell Toscanini you are to create this for me.” But cancer of the throat slowed the composer’s work and in November 9124 Puccini died without having completed the opera. When the work was finished by Alfano the world premiere was set for 1926. Again Toscanini summoned Martinelli, who pleaded in vain against the stone wall determination of Gatti-Casazza. “I do not stop you going,” he was told, “Only if you go do not return.” Once again Martinelli was thwarted. It had been thought that Giacomo Lauri-Volpi might substitute for Martinelli, but Gatti also refused him permission to go. Pertile was engaged outside of Italy in contracts which could not be broken, so Toscanini was forced to use Miguel Fleta, a splendid Spanish Lyric tenor, but one obviously unsuited for the dramatic demands of the Calaf. When, in 1927, the opera was brought to the U.S. Martinelli refused Gatti’s offer to sing it at the Metropolitan, and Lauri-Volpi was the one to create the part for America. Martinelli did not sing Turandot until 1937, when he sang performances with Eva Turner at Covent Garden.

Both at the Metropolitan, at San Francisco and at Chicago, Martinelli was acclaimed as having no equal in his own repertoire. At that time – 1917-1921, old timers will say that there was no difference in the public demand for tickets for Martinelli or those for Caruso. In some operas, such as Faust and Trovatore, Martinelli ranked alone. Caruso’s extreme top had become a bit jagged and he had difficulty with a sustained high B. Caruso did not sing Travatore at the Metropolitan after 1907, and the revival of 1914 of the opera featured Martinelli. The story of those rehearsals is told later.

After visiting Rio de Janiero in 1921, Martinelli helped form the San Francisco Opera Company in 1922, when under the baton of Gaetano Merola, he sang performances of Faust, Pagliacci and Carmen at Stanford University. The following year the opera company shifted to San Francisco and through 1939, Martinelli sang in the following operas in the coast city: Andrea Chenier, Travatore, Pagliacci, Aida, Forza del Destino, Otello, Juive, Boheme, Samson, Norma, Carmen, Ballo in Maschera and Tosca.

One of Martinelli's finest characterisations was the title role of Andrea Chenier. The opera was intended as a 1921 revival for Caruso, but upon Caruso's death it was decided to split the performances at the Metropolitan between Gigli and Martinelli. Let it be cited that no jealousy existed between these two tenors. They were close friends - the Martinelli daughters, Bettina and Giovanna attended the same schools as Gigli's daughter Rina, and the families were together constantly. Let me again quote from Martinelli's own talks on the composers he knew - this concerning Umberto Giordano, composer of Chenier:

"Umberto

Giordano was associated with me, or I with him, as the case

may be, throughout most of my career. In 1915 I first met him at the

rehearsals of Madame Sans-Gene at the Metropolitan where I assisted

in the world premiere with Farrar and Amato.

Again in 1922 I met him at the rehearsals of Fedora which we did with Jeritza and

then, lastly, at the performances of his most famous opera, Andrea

Chenier. I had not heard Chenier before I attanded some of the performances

at the Metrpolitan with Muzio, Danise and

Gigli. Later on, De Luca and Ruffo took

Gerard, Ponselle and Rethberg the

part of Madeleine and Lauri-Volpi and I sang the title

role.

"Umberto

Giordano was associated with me, or I with him, as the case

may be, throughout most of my career. In 1915 I first met him at the

rehearsals of Madame Sans-Gene at the Metropolitan where I assisted

in the world premiere with Farrar and Amato.

Again in 1922 I met him at the rehearsals of Fedora which we did with Jeritza and

then, lastly, at the performances of his most famous opera, Andrea

Chenier. I had not heard Chenier before I attanded some of the performances

at the Metrpolitan with Muzio, Danise and

Gigli. Later on, De Luca and Ruffo took

Gerard, Ponselle and Rethberg the

part of Madeleine and Lauri-Volpi and I sang the title

role.

I first heard Gigli and I left the theatre thoroughly downcast. 'Martinelli', I said to myself, 'How will you ever get the nerve to stand on that stage and sing Andrea Chenier after that glorious flood of sound you've just heard from Gigli.?' I voiced these doubts to Giordano who put his arms around my shoulder and said, 'Look , Giovanni, Gigli's voice is the most beautiful lyric tenor in the world today. If you tried to sing the same way, I'd say no. But you are gifted with a far more heroic voice. Chenier can be a dreamy poet, but he can also be a heroic figure. Make him that, and you will succeed. Here, let me emphasize how much verismo there is in this, the first of Giordano's aopera, written in 1896. Starting with the baritone soliquoy, Son sessant' anni through the Un di all'azzuro spazio of the tenor and continuing with such solos as Si fui soldato, La Mama morta of the soprano, Nemico della partria and Vecchia Madelon, the opera is built on dramatic recitative. Only in the lyric line of Come un bel di di Maggio and in the last part of the duet finale Vicino a te, does Giordano allow the lyric line to creep into his score.

But I return to the composer and what he told me. I took heart and sang as I imaginmed a soldier would sing and the public seemed to like this interpretation as well as that of the lyric poet. Let me tell you a funny episode involving my first preformance of Chenier which took place in the open air at Ravina Park, Chicago.

I had reached a point about three-quarters through the famous Improviso in the first act when suddenly all the lights went out leaving the stage, orchestra and audience in total darkness. I stopped and so did everybody else. Hurriedly the electricians were summoned and after a brief intermission the lights were restored. Maestro Papi, who was conducting, whispered to me, "Giovanni, da capo." I began the aria gain and had arrived at virually the same place when the lights failed for a second time. After they had been fixed I looked at the pit hoping the maestro would have decided to continue the performance following the conclusion of the aria. No such luck. Once again, Papi signalled da capo.

So I experienced the wildest possible success in my first Chenier, singing the Improviso three times. To this day I have been unable to decide whether it was audiences desire to hear the aria repeated which caused the lights to fail or whether some distant colleague 'put the horns on me'.

It is interesting to note that during their careers together (1913-1921) Martinelli and Caruso each sang Aida, Carmen, Pagliacci, Butterfly, Tosca, Boheme, Lucia, Manon Lescaut and Ballo in Maschera in the same seasons. Caruso also sang Prophete, Juive and Forza in the standard reportoire which Martinelli did not. Martinelli however sang Faust, Travatore and Lucia which Caruso no longer sang.

With the advent of Gigli, Martinelli continued to sing the same operas as before - but Gigli sang in Rigoletto, Traviata and Elisir dAmore which Martinelli did not. Gigli did not sing any dramatic parts at the Metropolitan until he came back at age 48 in 1938 when he did do two Aidas. But he never sang Pagliacci, Travatore, Carmen or Ballo on the Metropolitan stage.

Martinelli

sang more performances of leading parts than any other tenor in the history

of the Metropolitan. He sang a total or 650 performances at the New York

house and some 350 performances on tour with the Metropolitan. All in

all, Martinelli estimated he sang a total of 4,500 operatic performances

in his life. At the Metropolitan he sang 36 parts. His complete reportoire

was a total of 62 parts and he was learning the 63rd at the time of his

death. At the Metropolitan his record of performances are as follows:

Aida [90]; Carmen [56]; Pagliacci [45]; Travatore [44]; Faust [42]; Butterfly

[28]; Tosca [28]; Boheme [26]; Juive [26]; Otello [19]; Forza del Destino

[19]; Lucia [16]; Lakme [15]; Madam Sans-Gene [14]; Samson et Dalila

[14]; Simon Boccanegra [13]; Ernani [12]; L'Amore Dei Tre Re [12]; Manon

Lescaut [11]; Gioelli della Madonna [11]; Don Carlos [10]; Francesca

da Rimini [9]; Oberon [9]; Guglielino Tell [9]; Fedora [9]; Fanciulla

del West [9]; Gioconda [9]; Zaza [8]; Eugene Onegin [7]; La Campana Sommersa

[7]; Andrea Chenier [6]; Norma [6]; Goyescas [5]; Prophete [4]; Ballo

in Maschera [4]; Africana [2].

Martinelli

sang more performances of leading parts than any other tenor in the history

of the Metropolitan. He sang a total or 650 performances at the New York

house and some 350 performances on tour with the Metropolitan. All in

all, Martinelli estimated he sang a total of 4,500 operatic performances

in his life. At the Metropolitan he sang 36 parts. His complete reportoire

was a total of 62 parts and he was learning the 63rd at the time of his

death. At the Metropolitan his record of performances are as follows:

Aida [90]; Carmen [56]; Pagliacci [45]; Travatore [44]; Faust [42]; Butterfly

[28]; Tosca [28]; Boheme [26]; Juive [26]; Otello [19]; Forza del Destino

[19]; Lucia [16]; Lakme [15]; Madam Sans-Gene [14]; Samson et Dalila

[14]; Simon Boccanegra [13]; Ernani [12]; L'Amore Dei Tre Re [12]; Manon

Lescaut [11]; Gioelli della Madonna [11]; Don Carlos [10]; Francesca

da Rimini [9]; Oberon [9]; Guglielino Tell [9]; Fedora [9]; Fanciulla

del West [9]; Gioconda [9]; Zaza [8]; Eugene Onegin [7]; La Campana Sommersa

[7]; Andrea Chenier [6]; Norma [6]; Goyescas [5]; Prophete [4]; Ballo

in Maschera [4]; Africana [2].

Martinelli's career in the 1920s and

1930s with few exceptions was limited to America. The tenor regretted

this at a time when he had retired. "My management demanded so much

for me, that other than in America, no one could afford my fee",

he complained. This was the reason for the 18 year lapse between 1919

and 1937 in his Covent Garden appearances. Gatti held him back from going

to La Scala in Italy but he did sing in Roma in 1928-29 at the Constanzi,

appearing in Chenier, Aida, Forza del Destino, and La Campagna Sommersa

and also in Ernani, Chenier and Manot Lescaut at the Dal Verme in Milano.

He last sang in Italy in Bari in 1934 (Aida). He was asked to sing Parsifal

in 1940 at La Scala but the outbreak of the war ended that possibility.

He sang in Paris in 1937 and in Rio de Janiero in 1942. Canada also heard

him occassionally, but that was all for his international career.

Martinelli's career in the 1920s and

1930s with few exceptions was limited to America. The tenor regretted

this at a time when he had retired. "My management demanded so much

for me, that other than in America, no one could afford my fee",

he complained. This was the reason for the 18 year lapse between 1919

and 1937 in his Covent Garden appearances. Gatti held him back from going

to La Scala in Italy but he did sing in Roma in 1928-29 at the Constanzi,

appearing in Chenier, Aida, Forza del Destino, and La Campagna Sommersa

and also in Ernani, Chenier and Manot Lescaut at the Dal Verme in Milano.

He last sang in Italy in Bari in 1934 (Aida). He was asked to sing Parsifal

in 1940 at La Scala but the outbreak of the war ended that possibility.

He sang in Paris in 1937 and in Rio de Janiero in 1942. Canada also heard

him occassionally, but that was all for his international career.

His final actual performance at the Metropoliltan was in Norma in 1945 but he closed his Metropolitan career with Act.III of Boheme with Licia Albanese and John Brownlee in an Italian benefit in 1946. His last peratic performance was Samson et Dalila on January 24th, 1950 in Philadephia.

Late in his career, in 1939, he sang Tristan with Kirsten Flagstad in Chicago. Flagstad told this writer [Edward J Smith] that the 54 year old tenor sang with a lyric line and a perfection of legato of German diction which overwhelmed her. "This", Flagstad said, "was one of the great emoptional experiences of my entire career. I wish I could have sung much more with Giovanni Martinelli. He was the acolleague of colleagues."

Of the character of the tenor, I am perhaps in as good a position as anyone to judge, for in the past half century I have been witness to many episodes which showed him in his true light. Never, never, did I hear a harsh word of judgement passed on any colleague. He simply did not know how to speak evil of others. He only spoke when he could praise and one gathered if he had nothing to say, then he did not approve. He was a loving father to his two daughters and especially to his beloved Lele to whom he wrote faithfully every day. For the past score of years it was a ritual for me to carry his mail to him at 9.20a.m. every morning from Monday to Friday. On every one of those days, Giovanni Martinelli would be sitting up in bed drinking his morning coffee and writing to his beloved wife. Many were his old colleagues less fortunate financially then he, who on the Martinelli payroll. I remember one incident in Roma four years ago when he asked me to meet him at the Banco di Lavoro at 12 noon. I got there at 11.35 and Giovanni arrived at 11.45. He was angry when he saw me and told me to await him outside the bank.

At

that moment an old man aided by a cane came out of the bank. Martinelli

groaned in disgust. "Eddie, you were not here today. Remember that",

he said. We entered the bank and Martinelli drew out 500,000 lire (US$800)

and gave it to the old man, who dropped to his knees and tried to kiss

his hands. Martinelli, terribly embarrassed pulled away. He then introduced

us - "This is Manfredo Polverosi", he said.

Polverosi had been a slendid tenor who had sung much in Martinelli's

company in Italy and who had recorded extensively for Fonotipia. He was

then broke and destitute. This was but one of many aided by the great

tenor.

At

that moment an old man aided by a cane came out of the bank. Martinelli

groaned in disgust. "Eddie, you were not here today. Remember that",

he said. We entered the bank and Martinelli drew out 500,000 lire (US$800)

and gave it to the old man, who dropped to his knees and tried to kiss

his hands. Martinelli, terribly embarrassed pulled away. He then introduced

us - "This is Manfredo Polverosi", he said.

Polverosi had been a slendid tenor who had sung much in Martinelli's

company in Italy and who had recorded extensively for Fonotipia. He was

then broke and destitute. This was but one of many aided by the great

tenor.

Martinelli was godfather to my son, Eddie Jr. Once, when Eddie was three, Giovanni came over for his weekly visit and was immediately surrounded by a group of adults who clamoured for his attention. Eddie, holding a toy, tugged at his sleeve. Giovanno looked down and said, "Just a minute Eddie" ... Eddie walked off muttering, "I guess he does not like that toy, I'll get him another one". Martinelli overheard and a funny expression covered his face. When Eddie returned with a set of trains - Martinelli swept the adults to one side, and got down on his knees to play with the trains. For five minutes the blonde head of the three year old and the white head of the 75 year old were together on the floor before Martinelli rose kissing his Godson. He would not and could not disappoint a child who thought that he was there only for him.

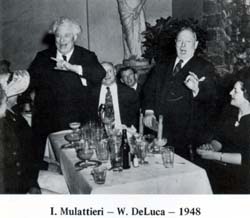

It is not for me to attempt to describe the Martinelli voice in its prime. To me it is the voice which gave me the greatest pleasure of all those I heard, and I started to attend opera at the Metropolitan in the 1914-15 season when I was a little past one year of age. I probably heard Martinelli sing in opera 500 times - maybe even more. It was my greatest honour to record him from 1950 to 1968 in a series of records which supassed in number those he made in his prime for the Victo company. The finest description of Martinelli's voice and of his singing I ever heard was expressed by his old colleague for 35 seasons, Giuseppe De Luca. Let me quote DeLuca:

I

have sung with Giovanni since 1914", he said. "Let me tell

you in his vocal prime his voice had a unique quality which was as individual

as that of Caruso. It was golden in hue and so ingratiating in its warmth

that it caressed the ear and that for a spinto is a remarkable thing.

Martinelli's diction, his phrasing and especially his breathing were

unique. I never heard any singer who had the enormous breath and line

which Martinelli possessed. He would sing phrase after phrase in a limpid

legato line which would leave the listener limp and gasping for breath.

His high register was magnificent and thrilling. The voice was an enormous

one to start with, with carrying quality which increased its volume the

further back one sat in a theatre. Martinelli reached a C or even a D

effortlessly and was able to sustain those notes with a brilliance which

defied description. Above all he was an artist in everything he sang

and he would deliberately make ugly sounds in his characterisations sucj

as in Juive, because the personality he was creating would have done

so. In his early days he was an ordinary actor. From 1930 on he was superb

and his Otello, Pagliacci, Samson et Dalila would have been magnificent

characterisations even if he just acted them. To me," said DeLuca

in conclusion, "the word nobility best describes Martinelli's art.

I would rank him as one of the three greatest tenors with whom I have

been associated."

I

have sung with Giovanni since 1914", he said. "Let me tell

you in his vocal prime his voice had a unique quality which was as individual

as that of Caruso. It was golden in hue and so ingratiating in its warmth

that it caressed the ear and that for a spinto is a remarkable thing.

Martinelli's diction, his phrasing and especially his breathing were

unique. I never heard any singer who had the enormous breath and line

which Martinelli possessed. He would sing phrase after phrase in a limpid

legato line which would leave the listener limp and gasping for breath.

His high register was magnificent and thrilling. The voice was an enormous

one to start with, with carrying quality which increased its volume the

further back one sat in a theatre. Martinelli reached a C or even a D

effortlessly and was able to sustain those notes with a brilliance which

defied description. Above all he was an artist in everything he sang

and he would deliberately make ugly sounds in his characterisations sucj

as in Juive, because the personality he was creating would have done

so. In his early days he was an ordinary actor. From 1930 on he was superb

and his Otello, Pagliacci, Samson et Dalila would have been magnificent

characterisations even if he just acted them. To me," said DeLuca

in conclusion, "the word nobility best describes Martinelli's art.

I would rank him as one of the three greatest tenors with whom I have

been associated."

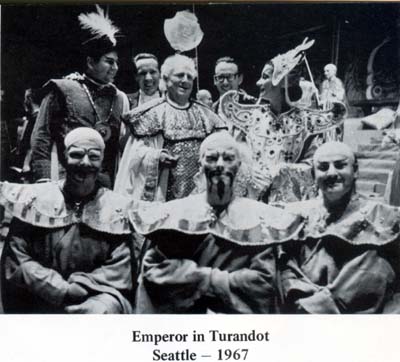

The

last years of Giovanni Martinelli's life were spent in lecturing with

the aid of phonograph records of his own and his old colleagues. He spoke

mostly on Verdi and on the composers he knew starting with Puccini. To

this end he went several times to London as well as the west coast of

the United States revisiting the cities where he has sung in past years.

In 1967, while in Seattle, the illness of a member of the cast of Turandot,

resulted in the tenor returning to the stage for the first time in 17

years. Martinelli sang the part of the Emporer, a part he knew well,

since the

The

last years of Giovanni Martinelli's life were spent in lecturing with

the aid of phonograph records of his own and his old colleagues. He spoke

mostly on Verdi and on the composers he knew starting with Puccini. To

this end he went several times to London as well as the west coast of

the United States revisiting the cities where he has sung in past years.

In 1967, while in Seattle, the illness of a member of the cast of Turandot,

resulted in the tenor returning to the stage for the first time in 17

years. Martinelli sang the part of the Emporer, a part he knew well,

since the  Emporer always talks to Calaf, the young prince, the principal

tenor part which Martinelli had sung in his younger years. The tenor

agreed to do one performance but finally acceeded to the demands that

he do all three - but he donated his fee to Italian Relief for the aid

of Florence, then recovering from the overflow of the River Arno. More

recently he was asked to accept the presidency of the London Opera Company

(Michael Scott, managing director) and also has been asked to return

to the stage this season once again in commemoration of his 60th anniversary

on the operatic stage. He decided he could do Leoni's L'Oracolo, which

he knew well since the opera usually preceeded the Pagliacci which he

sang at the Metropolitan. He wanted to do the basso part since it offered

better acting possibilities and was the part of an old man. He had started

to work hard on the music, which was transposed up for him a minor third

so it would lie well in the tenor key. He had just finished recording

a solo for the use of the Edison Company in a commemorative album of

his Edision records discussed with the executives of Edison, and he was

prepared with films of himself and of his colleagues to tour once again

to the west

coast (as far a Seattle, San Francisco and Los Angeles) in which he would

tell stories of his by-gone friends who silent and sound images would

be flashed on the screen with his own. Martinelli was the first great

artist to make sound films - his first having been made in 1926, a year

before Al Jolson's The Jazz Singer. Martinelli made a total of 20 such

films, some 13 of which have survived.

Emporer always talks to Calaf, the young prince, the principal

tenor part which Martinelli had sung in his younger years. The tenor

agreed to do one performance but finally acceeded to the demands that

he do all three - but he donated his fee to Italian Relief for the aid

of Florence, then recovering from the overflow of the River Arno. More

recently he was asked to accept the presidency of the London Opera Company

(Michael Scott, managing director) and also has been asked to return

to the stage this season once again in commemoration of his 60th anniversary

on the operatic stage. He decided he could do Leoni's L'Oracolo, which

he knew well since the opera usually preceeded the Pagliacci which he

sang at the Metropolitan. He wanted to do the basso part since it offered

better acting possibilities and was the part of an old man. He had started

to work hard on the music, which was transposed up for him a minor third

so it would lie well in the tenor key. He had just finished recording

a solo for the use of the Edison Company in a commemorative album of

his Edision records discussed with the executives of Edison, and he was

prepared with films of himself and of his colleagues to tour once again

to the west

coast (as far a Seattle, San Francisco and Los Angeles) in which he would

tell stories of his by-gone friends who silent and sound images would

be flashed on the screen with his own. Martinelli was the first great

artist to make sound films - his first having been made in 1926, a year

before Al Jolson's The Jazz Singer. Martinelli made a total of 20 such

films, some 13 of which have survived.

Martinelli refused to grow old. His savage "Io non voglio invecchiare" was his credo and he lived life to the hilt. His vigour was incredible and as will be seen his discs, he retained an amazing amount of voice for a man past 80 - even the high notes were there, to and including a sustained high B. I heard him sing this in December while giving a lesson to a pupil. He tried not to go above the staff while recording or in singing because, as he said, he had the notes, but who knew what went on with the machinery inside. He had been in magnificent health up to the night before his fatal attack. Even the morning of that attack he had been well. He had gotten up, made his own coffee, gotten his newspaper from the front door and gone back to bed to read and then write to his wife. At this point, the aorta snapped. Within an hour and a half he underwent open heart surgery, but the tear was too great - his bodily organs refused to function and while the great heart mheld out for four days, Giovanni Martinelli never regained consciousness. His life was music - and he was life personified.

Martinelli's death was reported on the

front page of the New York Times and included a full page review of his

career on the inside pages. This despite the fact that Martinelli has

not (aside from the performance of Turandot in Seattle), not performed

an opera since 1950. His wife and two daughters were at his bedside when

he died, and his body was returned to Rome (where his daughters lived),

for burial. This article has a fond, personal obituary to Martinelli: ![]()

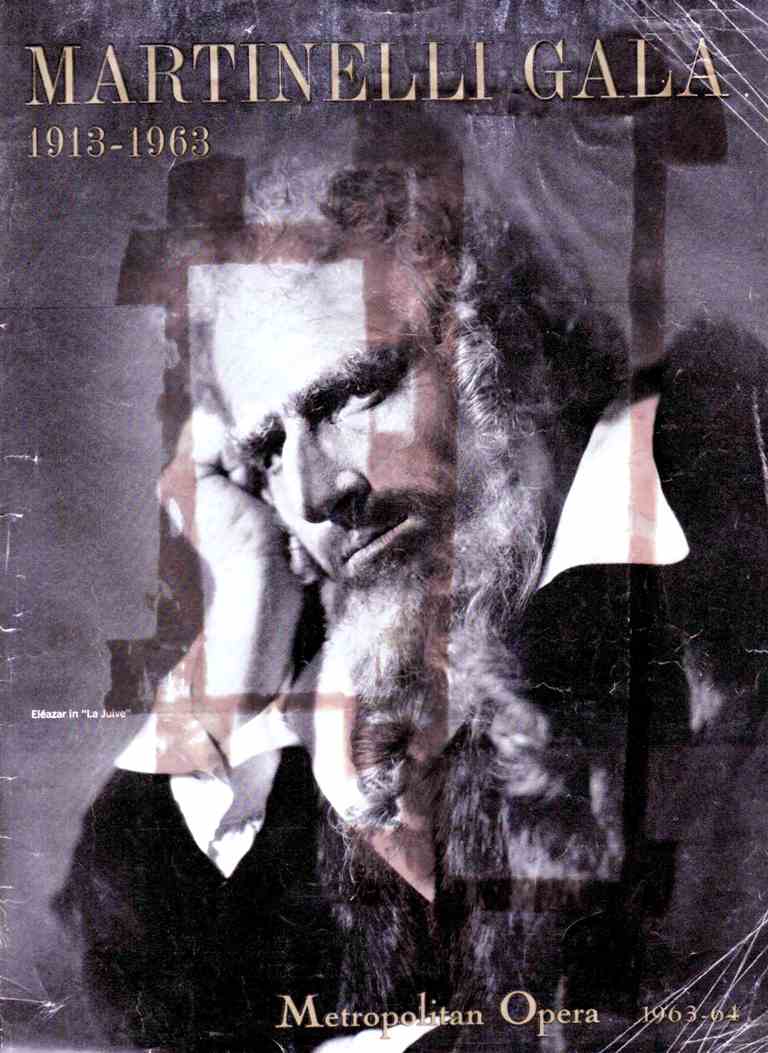

Martinelli Gala: 1913-1963

On Wednesday November 20th, 1963 at 8.00p.m. The Metropolitan Opera held a gala performance in honour of Giovanni Martinelli, 50 years after he first appeared there. Here are some scans of the program from that event and some reviews of the same.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

All material on danploy.com is the copyright of danploy.com (2004-2024) unless otherwise acknowledged.