.jpg)

Jackson Pollock: A problem for Iconography

Abstract

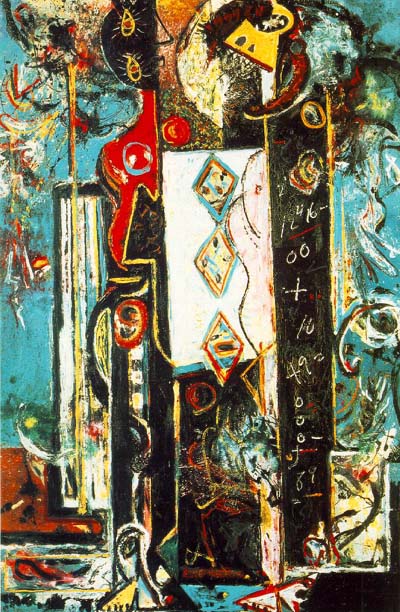

This essay will consider two recent texts on Jackson Pollock, by Sue Taylor, (2003), and Suzette Doyon-Bernard (1997). The latter article offers us a detailed iconographic analysis of one of his earlier works, Male and Female (1942), comparing the various motifs and symbols with Peruvian Chavin art, and in particular the Tello Obelisk. The former article analyzes the motifs and symbols in Pollock’s, Stenographic Figure, (1942).

Introduction

A number of artists that later would become known as the Abstract Expressionists, (e.g. Rothko, Barnett Newman, Still and Pollock), wrote about their belief in the use of archaic symbols,

‘We assert that the subject is crucial and only that subject-matter is valid which is tragic and timeless. That is why we profess spiritual kinship with primitive and archaic art.’

It is known that these New York based artists frequented the American Museum of Natural History and studied other ethnographic material, including specifically Chavin art so the analysis of Doyon-Bernard therefore seems apt and appropriate.

Doyon-Bernard’s

article analyzes a work by Jackson

Pollock, Male and Female, that has proven somewhat enigmatic in its

interpretation, particularly as Pollock himself was reluctant to ‘explain’ his

work: for example there is still discussion over the identity of the

male and female figure (see below). The work has attracted a number

of approaches to its explanation: Pollock’s interest in Jungian

principles offering a possible

psycho-analytical stance, or a feminist approach could be offered by

the possibility that the figures represent surrogates for Lee Krasner

(who he had recently met), and Pollock himself.

Doyon-Bernard’s

article analyzes a work by Jackson

Pollock, Male and Female, that has proven somewhat enigmatic in its

interpretation, particularly as Pollock himself was reluctant to ‘explain’ his

work: for example there is still discussion over the identity of the

male and female figure (see below). The work has attracted a number

of approaches to its explanation: Pollock’s interest in Jungian

principles offering a possible

psycho-analytical stance, or a feminist approach could be offered by

the possibility that the figures represent surrogates for Lee Krasner

(who he had recently met), and Pollock himself.

Stenographic Figure has also been interpreted variously as Taylor explains in her article: for example there is still argument about whether one or two figures are present in the painting. Pollock’s personal psychoanalysis leads a number of art critics to try to interpret the symbols in this painting, and all Pollock’s work, as for Jung these are indicative of the deepest psyche of the artist, an inherited ‘collective unconscious’. William Rubin criticism of this, which I believe can be applied generally to an iconographic analysis of Pollock’s work, is the habit of forcing images ‘so that one finds in them what one is looking for’: clearly, as any reading of the various articles on Pollock shows, there is no consistent or unambiguous translation of the motifs and symbols. Pollock replying in 1943 to a question in a questionnaire stated ,

‘I have always been very impressed with the plastic qualities of American Indian art. The Indians have the true painter’s approach in their capacity to get hold of appropriate images, and in their understanding of what constitutes painterly subject matter. Their colour is essentially Western, their vision has the basic universality of all real art. Some people find references to American Indian art and calligraphy in parts of my pictures. That wasn’t intentional; probably was the result of early memories and enthusiasms.’

Ernst Gombrich elaborates this point in exploring the relationship between symbols of a real horse and a hobby horse . As Hasenmueller elucidates, Panofsky’s method reduces meaning to the metaphoric, an association between the representation and the represented. For Gombrich this is only half the problem solved, the likeness between the motif and ‘real’ object does not imply they have the same function. The hobby horse can be ridden and so can the horse, but the function of each is different, and could not be implied from the symbol.

Male and Female: Gender identification

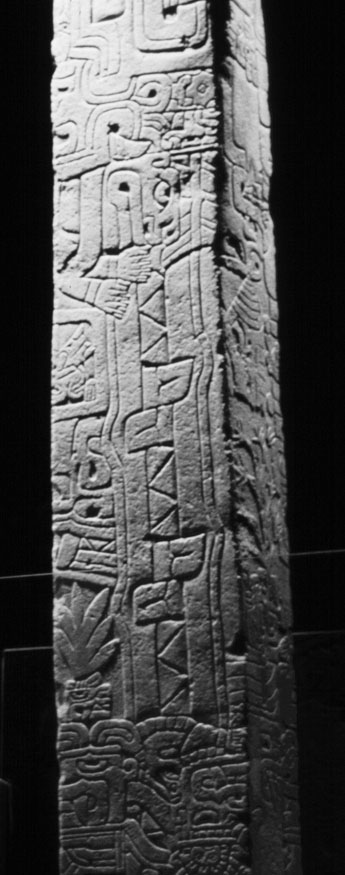

The

Tello obelisk, has two vertical figures which have been identified

as caimans, an alligator like semi-aquatic reptile, indigenous to South

America. The two figures themselves are masked by a multitude of secondary

symbols and motifs and discerning the larger figure somewhat difficult.

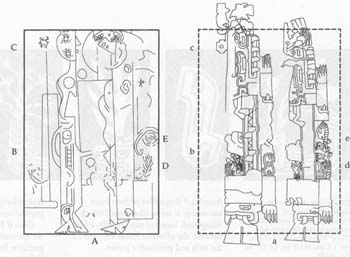

Doyon-Bernard has produced a line drawing comparison of Pollock’s

painting and the obelisk to compare the motifs, using the obelisk as

the point of reference. Julio Tello, who discovered the obelisk, says

the male caiman was associated with the sky and the rainy season, whilst

the female figure represented the earth and the dry season and

Tello also claims to have identified the genitalia of the supernatural

creatures, identifying item ‘d’ as the phallus and ‘e’ as

the female genitalia. However Elizabeth Langhorne has identified a

phallus on the left-hand figure and associates the yellow triangle

on the right-hand figure as the female genitalia.

Langhorne claims that Pollock associated red with the male and yellow

with the female and uses the fact that the figures contain both colours

allude to a ‘union of opposites’, a joining of the Jungian

concepts of animus and anima. However this colour reading seem apposite

to Jungian interpretation where yellow represents intuition and red

represents emotion or feeling, both traditional female attributes.

The

Tello obelisk, has two vertical figures which have been identified

as caimans, an alligator like semi-aquatic reptile, indigenous to South

America. The two figures themselves are masked by a multitude of secondary

symbols and motifs and discerning the larger figure somewhat difficult.

Doyon-Bernard has produced a line drawing comparison of Pollock’s

painting and the obelisk to compare the motifs, using the obelisk as

the point of reference. Julio Tello, who discovered the obelisk, says

the male caiman was associated with the sky and the rainy season, whilst

the female figure represented the earth and the dry season and

Tello also claims to have identified the genitalia of the supernatural

creatures, identifying item ‘d’ as the phallus and ‘e’ as

the female genitalia. However Elizabeth Langhorne has identified a

phallus on the left-hand figure and associates the yellow triangle

on the right-hand figure as the female genitalia.

Langhorne claims that Pollock associated red with the male and yellow

with the female and uses the fact that the figures contain both colours

allude to a ‘union of opposites’, a joining of the Jungian

concepts of animus and anima. However this colour reading seem apposite

to Jungian interpretation where yellow represents intuition and red

represents emotion or feeling, both traditional female attributes.

These opposing interpretations will arise: Pollock was not part of the same cultural or historical group as those who created the Tello obelisk and he therefore could not share the same tacit knowledge as them : equally modern day art historians are distanced from both of the above.

Stenographic Figure

Sue Taylor’s article discusses Pollock’s painting, Stenographic Figure, 1942, the same year that he painted Male and Female.

Taylor considers the various approaches and interpretations for the painting in her article, from the pre-iconographic description of O’Connor to the psycho-analytical by Naifeh and Smith, whilst also offering her own lucid comment,

‘If Pollock injected “willed confusions” into Stenographic Figure, he did so ingeniously, leaving generations of viewers uncertain about its specific subject matter and content.’

Langhorne again tries to ‘explain’ the

various motifs in the painting through Jungian analysis ; ‘Thus

the numerical formula 66=42 can be seen as yet another statement of

Pollock’s desire for a union of opposites’ ,

something Rubin attributes to ‘compositional needs’. Taylor

chooses the middle ground here and concentrates on a more literal explanation

of the painting through its title: the painting is of a stenographer

and the symbols on the painting are the result of the recording of

shorthand. However the validity of this could be called in question

once one realizes the painting was originally called just that, Painting

, although it was Pollock that renamed it in 1943 .

Langhorne again tries to ‘explain’ the

various motifs in the painting through Jungian analysis ; ‘Thus

the numerical formula 66=42 can be seen as yet another statement of

Pollock’s desire for a union of opposites’ ,

something Rubin attributes to ‘compositional needs’. Taylor

chooses the middle ground here and concentrates on a more literal explanation

of the painting through its title: the painting is of a stenographer

and the symbols on the painting are the result of the recording of

shorthand. However the validity of this could be called in question

once one realizes the painting was originally called just that, Painting

, although it was Pollock that renamed it in 1943 .

Even if we accept the literal Jungian interpretation of the symbols, how can we be sure that Pollock was not consciously manipulating them: the symbols lose their meaning if they are not unconscious acts? Varnedow notes : whether Pollock’s works, ‘contain consciously coded references to doctrine or involuntary exhumations of predictable symbolic structures.’ Taylor adds doubt to the symbols interpretation by suggesting that Stenographic Figure is an allegory for Pollock’s relationship with his psychotherapist and his apparent lack of autonomy in his artistic work: his work is suggested as being just a derivative of his unconscious.

If Pollock was trying to shake off the unconscious act that Jung’s followers attributed to painting, where the artist was just a stenographer, and move to Greenbergian autonomy, then any absolute interpretations of symbols in his paintings should be cautioned.

A year later in 1943, Pollock produced

the painting, Guardians of the Secret. This work appears to combine

both Male and Female (having two mythic symbols representing human

figures), and Stenographic Figure (by showing tablet covered in figures).  However

here the symbols have deliberately no Jungian significance, Pollock

has stated his autonomy. As Kuspit writes, the artists despairing ‘sense

of meaningless becomes dominant and overt in the all-over paintings,

which is what makes them truly untranslatable and uninterpretable’ ,which

Taylor goes on to add is ‘a frightening prospect to art historians’.

However

here the symbols have deliberately no Jungian significance, Pollock

has stated his autonomy. As Kuspit writes, the artists despairing ‘sense

of meaningless becomes dominant and overt in the all-over paintings,

which is what makes them truly untranslatable and uninterpretable’ ,which

Taylor goes on to add is ‘a frightening prospect to art historians’.

Conclusion

Panofsky’s iconography is in opposition to the formalist approaches of Wofflin or Greenberg and fall short of a deeper contextual social-historical analysis offered by, for example, Baxandall. Iconography is an attempt to bring science to art history, to offer an empirical analysis of painting without humanistic concerns. Panofsky’s iconology watered down these boundaries, and his concerns were shown when he writes, ‘There is admittedly some danger that iconology will behave, not like ethnology as opposed to ethnography, but like astrology as opposed to astrography.’

Modern day art historians are still using iconography to bring meaning to paintings and this essay considers two such analyses, one comparing Pollock’s painting Man and Women with Chavin art, and the other looking at interpretations of his painting, Stenographic Figure, particularly from the Jungian perspective.

We can see from Taylor’s article that it is dangerous to apply such an explicit ‘reading’ of Pollock’s painting. We know now that the paintings considered were transition paintings on the way to the drip paintings and Pollock was fighting to achieve his autonomy and not to be a pawn of his Jungian subconscious: he was trying to obliterate the meaning of the symbols in painting. The dedicated iconographer will try to show that Pollock ‘over-painted’ the symbols, even on his most abstract works, still allowing them to be understood. But given Pollock’s intentions an iconographic reading is certainly, at best, open to interpretation, and at worst misleading. Pollock stated, in talking about his painting She Wolf of 1944, the painting ‘came into existence because I had to paint it. Any attempt on my part to say something about it, to attempt an explanation of the inexplicable, could only destroy it.’

Such interpretations of Pollock’s

paintings distil the impact of the work, and go against the formalist

instantaneousness of Michael Fried. An iconographic reading of an image

supposes a degree of naturalism in its realization and largely only

works when the work is a narrative representation of literary subjects.

Panofsky's methods relate 'text' to 'image' and could form the basis

of a semiotic reading of the image. However relating literary analysis

to images assumes images are read narratively and not realized instantaneously.

Indeed, it was the association of text with image that opened up the

possibility of a semiotic reading of images.

Such interpretations of Pollock’s

paintings distil the impact of the work, and go against the formalist

instantaneousness of Michael Fried. An iconographic reading of an image

supposes a degree of naturalism in its realization and largely only

works when the work is a narrative representation of literary subjects.

Panofsky's methods relate 'text' to 'image' and could form the basis

of a semiotic reading of the image. However relating literary analysis

to images assumes images are read narratively and not realized instantaneously.

Indeed, it was the association of text with image that opened up the

possibility of a semiotic reading of images.

However, if iconography cannot be applied to Pollock’s work, if it appears to have no narrative does it mean his work does not ‘mean’ anything? I do not believe so. Pollock stated, when questioned how a viewer should approach his art, ‘I think they should not look for, but look passively – and try to receive what the painting has to offer and not bring subject matter or preconceived idea of what they are to be looking for.’ Iconography, by studying the minutiae of its symbolism, prevents being engulfed by the work, to be drawn in and by so doing, to be absorbed into its ‘big idea’. Abstract artists own intentions are often stated that their wish is to convey the big idea, and their removal of artwork names and their increasing abstraction were done to convey this as effectively as possible. Therefore if we continue to analyse these works iconographically we lay ourselves open to the possibility of the ‘intentional fallacy’, that we are reading motive into a work that was not the artist’s intention. As Rothko wrote, 'The familiar identity of things has to be pulverized in order to destroy....finite associations' . William Wright, in a radio interview, asked Pollock , ‘Then deliberately looking for any known meaning or object in an abstract painting would distract you immediately from ever appreciating it as you should.’ To which Pollock replied, ‘I think it should be enjoyed just as music is enjoyed – after a while you may like it or you may not.’

Rosemblum wrote of Rothko’s painting, they offer us a depiction of, 'the awe-inspiring infinities of the natural world as a metaphor of the supernatural world beyond' . As such any symbols present would deter us from 'looking beyond', and looking for them distracts us from the true meaning and effect of these great works.

Notes

Mark Rothko 1903-1970, pp.69. This was part a letter in the New York Times, written by Rothko and Gottlieb, in response to a review of Rothko’s The Syrian Bull and Gottlieb’s Rape of Persephone by Edward Alden Jewell.

Doyon-Bernard, Suzette, Jackson Pollock: a Twentieth Century Chavin Shaman

Pollock had attended his first psychoanalysis in 1937, and in 1939 visited Dr. Joseph Henderson for psychotherapy, who was an analysand of Yung (Interpreting Pollock, pp.16).

Taylor, Jackson Pollock’s Stenographic Figure, pp.55.

Art in Theory 1900-2000, pp.570.

See Hasenmueller, Panofsky, Iconography and Semiotics, pp.292, Footnote no.19.

Doyon-Bernard, Suzette, Jackson Pollock: a Twentieth Century Chavin Shaman, pp.13.

Taylor, Jackson Pollock’s Stenographic Figure, pp.60.

See Hasenmueller, Panofsky, Iconography and Semiotics, pp.292.

Taylor, Jackson Pollock’s Stenographic Figure, pp.53.

Taylor, Jackson Pollock’s Stenographic Figure, pp.53.

Taylor, Jackson Pollock’s Stenographic Figure, pp.57.

The Chinese symbol Tao, is understood in Jungian terms to stand for the ‘union of opposites’.

Taylor, Jackson Pollock’s Stenographic Figure, pp.64.

Taylor, Jackson Pollock’s Stenographic Figure, pp.61.

Taylor, Jackson Pollock’s Stenographic Figure, pp.69.

Art in Theory 1900-2000, pp.584.

Art in Theory 1900-2000, pp.584.

Bibliography

Bal, Mieke and Bryson, Norman, Semiotics and Art History: A discussion of Context and Senders, reproduced in The Art of Art History: A Critical Anthology, edited by Preziosi, Donald, (Oxford University Press, 1998).

Bal, Mieke; Yve-Alain Bois; Irving Lavin; Griselda Pollock; Christopher S. Wood, Art History and Its Theories, The Art Bulletin, (Vol. 78, No. 1. Mar., 1996), pp. 6-25.

Barolsky, Paul; Carrier, David; Gaskell, Ivan, Kosuth, Joseph; Schele, Linda, Writing (and) the History of Art, The Art Bulletin, (Sept. 1996, Vol.78, No. 3), pp.398-416.

Damisch, Hubert, Semiotics and Iconography, reproduced in The Art of Art History: A Critical Anthology, edited by Preziosi, Donald, (Oxford University Press, 1998).

Desai, Devangana , Monumental Legacy, Khajuraho, ( Oxford University Press, 2004).

Desai, Devangana, Puns and Enigmatic Language in Sculpture, Reading 3.3 from A840, The PostGraduate Foundation Module in Art History, (The Open University, 2005), pp.3.3.1-3.3.27.

Doyon-Bernard, Suzette, Jackson Pollock: a Twentieth Century Chavin Shaman, American Art, Vol. 11, No. 3. (Autumn, 1997), pp. 8-31

Fernie, Eric, (selection and commentary), Art History and its Methods, (London: Phaidon Press Limited, 1999).

Harrison , Charles and Wood, Paul, Art in Theory 1900-2000, An Anthology of Changing ideas, (Blackwell Publishing, 2003).

Hasenmueller, Christine, Panofsky, Iconography, and Semiotics,The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, (Vol. 36, No. 3, Critical Interpretation, Spring, 1978), pp. 289-301.

Holmes, Megan, Disrobing, the Virgin: The Madonna Lactans in Fifteenth-century Florentine Art Reading 3.4 from A840, The PostGraduate Foundation Module in Art History, (The Open University, 2005), pp.3.4.1-3.4.25.

King, Catherine, Iconographic Approaches: Interpretations and Meanings, A840 Postgraduate Foundation Module in Art History, (The Open University, 2005), pp.3.1-3.34.

Langhorne, Elizabeth, The Magus and the Alchemist: John Graham and Jackson Pollock, American Art, (Vol. 12, No. 3, Autumn, 1998), pp. 46-67.

Lewison, Jeremy, Interpreting Pollock, (Tate Gallery Publishing, 1999).

Morrogh, Andrew, The Magnifici Tomb, A Key Project in Michelangelo’s Architectural Career, The Art Bulletin, (Dec. 1992, Vol. LXXIV, No.4), pp.567-596.

Panofsky, Erwin, Iconography and Iconology, Reading 3.1 from A840, The PostGraduate Foundation Module in Art History, (The Open University, 2005), pp.3.1.1-3.1.4.

Panofsky, Erwin, The NeoPlatonic Movement and Michelangelo, Reading 3.2 from A840, The PostGraduate Foundation Module in Art History, (The Open University, 2005), pp.3.2.1-3.2.23.

Preziosi, Donald, Mechanisms of Meaning: Iconography and Semiology, The Art of Art History: A Critical Anthology, edited by Preziosi, Donald, (Oxford University Press, 1998).

Tate Gallery Publishing (ed.), Mark Rothko 1903-1970, (Tate Gallery Publishing, 1999).

Taylor, Sue, The Artist and the Analyst: Jackson Pollock’s “Stenographic Figure”, American Art, (Vol. 17, No. 3. Autumn, 2003), pp. 52-71.

Woodfield, Richard, The Essential Gombrich, Selected writings on Art and Culture, (London, Phaidon Press, 1996).

All material on danploy.com is the copyright of danploy.com (2004-2024) unless otherwise acknowledged.