.jpg)

Resurrecting Modernism

I used to be a quite regular visitor to the Tate Modern Gallery in London, something now curtailed by my move to Singapore. Most of the visits were opportunistic: usually I was in London for another reason and I did not expressly visit to see any particular special exhibition. As such I tended to wander without much purpose, happening upon old friends (“Oh good you are still here, how are you? I have missed you: Are they taking care of you?”), and if lucky discovering a new hanging by a favourite artist or one I had previously missed. The works that engender this warmth and familiarity, and also produce the ‘Wow’ factor are produced by a relatively few number of artists and in this essay I will examine why it is only they that give me this experience.

Before

attempting to answer these questions I should declare which are the

works that do and do not give me this experience. Well, works that ‘do’ are

by Rothko, Pollock, Mondrian, Kandinsky and Miro (not an exclusive

list and apologies to those I have missed); and works that ‘don’t’ include

Whiteread, Naumann and Hirst. I mention this because in my research

for this article I find the question of what is, in art, beautiful

and what is not, discussed in philosophical circles but not in art

history ones. For example I have just completed a one year degree level

course in art history of the 20th century (Open University AA318 and

I also previously completed a modern art course from the same university,

A316) and in neither course was this issue discussed. However in the

philosophical debates I can find no specific instances discussed, the

issues are discussed in generic terms, usually including literature

and music as well. This essay will discuss the issue from a purely

art historical perspective.

Before

attempting to answer these questions I should declare which are the

works that do and do not give me this experience. Well, works that ‘do’ are

by Rothko, Pollock, Mondrian, Kandinsky and Miro (not an exclusive

list and apologies to those I have missed); and works that ‘don’t’ include

Whiteread, Naumann and Hirst. I mention this because in my research

for this article I find the question of what is, in art, beautiful

and what is not, discussed in philosophical circles but not in art

history ones. For example I have just completed a one year degree level

course in art history of the 20th century (Open University AA318 and

I also previously completed a modern art course from the same university,

A316) and in neither course was this issue discussed. However in the

philosophical debates I can find no specific instances discussed, the

issues are discussed in generic terms, usually including literature

and music as well. This essay will discuss the issue from a purely

art historical perspective.

The title of the this essay is Resurrecting Modernism, and will therefore start by defining what is, and what isn’t, in my opinion, Modernism, and why for me it is the one art historical theory that holds water, not just in the 1950s when it was the pre-eminent theory but also for the now and for the future. I will look at some artists that I believe were prime instigators in the creation of Modernist art, and also some that were not and try to analyze why they were not. And lastly I will look at the question that Modernism was an art theory of its time that has no place in today’s contemporary society.

There are several things in common with the favoured works, they are paintings, largely abstract, they were painted in the first two thirds of the twentieth century, the painters are recognised as being significant contributors to the canon of twentieth century art and they were all lauded by the influential American art critic Clement Greenberg and as such have (retrospectively in some cases) been included in the Modernist canon. The dominance of Modernism as the principal art critical movement of the twentieth century disintegrated in the late sixties leading to a disparate range of movements (if I can call them that), including conceptual art, performance art, minimalist art etc. etc. exemplified by their non-medium specificity (i.e. move away from painting). Modernism at this time turned from the passive critique of Greenberg to the more aggressive defence of Michael Fried, but although attempts have been made to merge it with other critical thinking I think, today, it is now regarded as a discredited theory with all the juice rung from it. However no encompassing art critical theory includes all of the later movements and we can only categorize them by saying they are not-Modernist (as opposed to post-Modernist). The Greenbergian definition of Modernism was of the work having flatness which, of course, confines a Modernist work to painting only, although Fried did later include the sculptures of Caro, mistakenly in my view.

Other art theories abound, feminism, queer theory, semiotics, iconography, social, cultural, Baxandalian, psychoanalytical; but all of these has tried to be applied to all art. Panofsky never tried to apply his theory of iconography outside of Renaissance and early Netherlandish art, but latterly others have applied to other, less suitable, art forms.

The

difference between Modernism and these other art theories is the value

judgment. Modernism states what is the most beautiful art: allows the

viewer to judge, allows the institution or museum to judge. Interestingly,

most of these other theories cannot be usefully applied to a true Modernist

work. Iconography requires recognizable motifs, semiotics requires

a text, a narrative to the painting, for its literal analysis to work.

Of course the charge can be made that Modernism is elitist, you have

to have knowledge to value the work. Of course what I am alluding here

is a charge that is often placed on Modernist work, and that is the

claim of elitism: as stated in the Tanner Lecture, ‘Modernism… makes

being difficult and inaccessible a virtue’. I find the charge

of elitism irrelevant and unfair: it is the works autonomy and near

aloofness that adds to its intrigue: it is not the fault of the work

or the artist that such works give this experience and others do not.

However I do agree that you need to approach a Modernist work with

a certain openness, a child’s view if you like. It is an oft

quoted statement that, ‘my five year old child could have painted

this”: no they could not, but they are possibly the best to view

it, unfettered as they are by formal logic. The charge of elitism seems

to also infer conservatism as opposed to the progressive, Marxist driven

art which provides a societal comment. But there is room for both forms

of art, my concern here is only in being able to say which is beautiful

and which is not, not which is the better art (although I have made

it clear than for me the former is ‘better’).

The

difference between Modernism and these other art theories is the value

judgment. Modernism states what is the most beautiful art: allows the

viewer to judge, allows the institution or museum to judge. Interestingly,

most of these other theories cannot be usefully applied to a true Modernist

work. Iconography requires recognizable motifs, semiotics requires

a text, a narrative to the painting, for its literal analysis to work.

Of course the charge can be made that Modernism is elitist, you have

to have knowledge to value the work. Of course what I am alluding here

is a charge that is often placed on Modernist work, and that is the

claim of elitism: as stated in the Tanner Lecture, ‘Modernism… makes

being difficult and inaccessible a virtue’. I find the charge

of elitism irrelevant and unfair: it is the works autonomy and near

aloofness that adds to its intrigue: it is not the fault of the work

or the artist that such works give this experience and others do not.

However I do agree that you need to approach a Modernist work with

a certain openness, a child’s view if you like. It is an oft

quoted statement that, ‘my five year old child could have painted

this”: no they could not, but they are possibly the best to view

it, unfettered as they are by formal logic. The charge of elitism seems

to also infer conservatism as opposed to the progressive, Marxist driven

art which provides a societal comment. But there is room for both forms

of art, my concern here is only in being able to say which is beautiful

and which is not, not which is the better art (although I have made

it clear than for me the former is ‘better’).

However, as I have noted, the works that for me produce that ‘Wow factor’, that I do put the greatest worth to, are Modernist works, so before dismissing the theory, lets look at a non-Modernist work.

When Panofsky extended his iconographical methods to iconology, his third method, he was aware of the problems he was inviting: he likened the possible outcome to that of astrography becoming astrology. And at the time he was writing, (the 1950s), he was aware that the charge of being unscientific could be brought, discrediting his whole theory. Iconology, Panofsky wrote, relies on intuition.

Today we live in world of science and pseudo-science: there is no mystery anymore: religion is dying and anyone who steps outside the norm is regarded as a crank. The problem with abstract art is it does not fit with this society: it requires a suspension of belief: we have to stop analyzing and interpreting and ‘go with flow’, wherever it takes it us. Appreciation of abstract art may require society to return to more Humanist times, to Croce’s pillars of the Beautiful, the True, the Useful and the Good. Abstract art was born from a society in need of the spiritual and died when society felt it no longer needed that.

The

non-representational Modernist paintings reward repeated viewing. Because

they do not represent anything, every time I view them I get something

new from them, they are mirrors to my emotions, they are elusive, the

deeper I go into them the more there is to find. The Modernist works

have a beauty which gives me that ‘instant’ reaction, but

their beauty also draws you in, it is a gateway to higher experience,

and this experience, hinted at in previous experiences is what draws

you back like a drug, each time it is possible to glimpse a little

more, never is it wholly revealed. And it is the stillness of the painting

that allows us to draw more from it; Fried talks of the work being ‘wholly

manifest’ to the viewer and this is achieved through the paintings

stillness, allowing the viewer to contemplate and absorb without distraction:

this is a unique property of painting (even sculpture, because of its

three dimensionality, invites the viewer to walk around the work, it

is not ‘wholly manifest’), and stillness is often given

as an attribute of beauty. In a sense the non-representational painting

exists not so much as an object in itself but as a prompt for internalised

images and ideas, a window or, better, a mirror on the mind. This internalisation

of experience is in contrast to the experience for non-Modernist work

which is played out in the public space and as such mediated. I subscribe

to the view of Plotinus, who asks that art reveal more of the form

of an object than ordinary experience, raising the soul to contemplation

of the universal. The German philosopher Immanuel Kant proposed that

beautiful objects should produce a disinterested unselfish desire which

I believe non-Modernist works cannot produce because of the engagement

required on behalf of the viewer.

The

non-representational Modernist paintings reward repeated viewing. Because

they do not represent anything, every time I view them I get something

new from them, they are mirrors to my emotions, they are elusive, the

deeper I go into them the more there is to find. The Modernist works

have a beauty which gives me that ‘instant’ reaction, but

their beauty also draws you in, it is a gateway to higher experience,

and this experience, hinted at in previous experiences is what draws

you back like a drug, each time it is possible to glimpse a little

more, never is it wholly revealed. And it is the stillness of the painting

that allows us to draw more from it; Fried talks of the work being ‘wholly

manifest’ to the viewer and this is achieved through the paintings

stillness, allowing the viewer to contemplate and absorb without distraction:

this is a unique property of painting (even sculpture, because of its

three dimensionality, invites the viewer to walk around the work, it

is not ‘wholly manifest’), and stillness is often given

as an attribute of beauty. In a sense the non-representational painting

exists not so much as an object in itself but as a prompt for internalised

images and ideas, a window or, better, a mirror on the mind. This internalisation

of experience is in contrast to the experience for non-Modernist work

which is played out in the public space and as such mediated. I subscribe

to the view of Plotinus, who asks that art reveal more of the form

of an object than ordinary experience, raising the soul to contemplation

of the universal. The German philosopher Immanuel Kant proposed that

beautiful objects should produce a disinterested unselfish desire which

I believe non-Modernist works cannot produce because of the engagement

required on behalf of the viewer.

My struggle describing my experience in front of a Modernist work could perhaps point us in the direction of a value judgement for art. Wittgenstein wrote, ‘aesthetic judgements about what is beautiful cannot be expressed within a logical language since they transcend what can be pictured in thought: they aren’t facts.’ I struggle to find the words to describe a Rothko because to describe the painting is to describe the feelings I have for the painting. But for non-Modernist works there is only the description, there is nothing more. Non-Modernist works either ‘work’ or don’t: a verdict is reached or a conclusion is found. Abstract art has infinite layers and defies conclusion, it is an enigma, which is why it intrigues and why it warrants return visits. It is not the artwork on the wall but my reaction to it that I am exploring which is why it is different every time I view it. Modernist works invite us to view the painting aesthetically: if we view a painting with the aim of valuing it we do not bring to it an aesthetic eye, non-Modernist works also refuse this aesthetic engagement because viewer has to go through a process to understand them, they do not have the immediacy that beauty has.

As

a contrast to the favoured Modernist works I would like to consider

the sculptures of Rachael Whiteread. To be honest I had largely ignored

her work on early visits to the Tate. However, in some ways forced

to examine them closer with a fellow student, I started to have a certain

curiosity about them. The sculptures of the spaces between did seem

to capture some essence of the people that were once there and they

certainly rewarded the closer inspection.

As

a contrast to the favoured Modernist works I would like to consider

the sculptures of Rachael Whiteread. To be honest I had largely ignored

her work on early visits to the Tate. However, in some ways forced

to examine them closer with a fellow student, I started to have a certain

curiosity about them. The sculptures of the spaces between did seem

to capture some essence of the people that were once there and they

certainly rewarded the closer inspection.

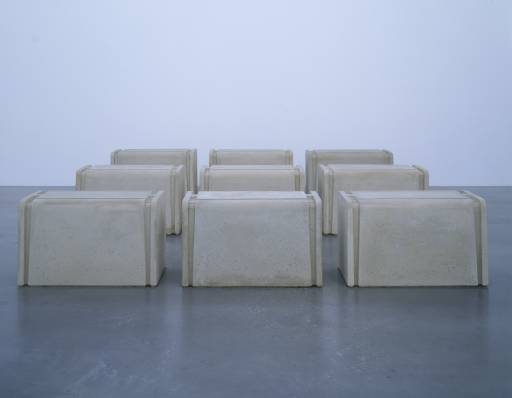

Whiteread’s work, Nine Tables, is a sculpture of the void between objects: she displays what is in effect the back of the Limewood Sculptor’s figures. The material she uses is also of particular relevance; the softness of the wooden tables is replaced by the hardness of concrete and the method of manufacture, an automatic process replacing the handcraft of the original, deliberately removing the mark of the artist, blurring the boundary between what is ‘high art’ and what is craft. The intimate domesticity of the originals locations is also removed as the work is intended for display in a public place and the transitory nature of the originals are replaced by a massiveness and permanence. The inverted works also capture an action, what actually happened at the tables rather than just a cast of the objects themselves, they are ‘reliquaries to the unknown living’ or to quote Sue Malvern, they are ‘metaphors for the human body’.

However the work did not give me Fried’s ‘instantaneousness’, they needed time, they needed some explanation; without the explanatory plaque on the wall I wouldn’t know what they were of, and therefore would not have been able ‘get into’ the work, to start imagining the lives of those who had inhabited those spaces, and the work is not comprehensible without the explanation, and without that comprehension it does not appear to ‘stand alone’ as work. So the work does not give me that immediacy that Fried requires, and certainly it does involve me in his theatre, I need to walk around the work to be able to see the subtle impression in the concrete (something the Tate now largely thwarts), dispersing and de-intensifying the experience. The Italian Benedetto Croce also writes of the ‘immediate awareness’ of an object giving the object form. The next time I visit the work I may notice one or two things I did not notice first time but there will be a time when there is nothing more to be found and if I spent enough time on my first visit that would be it, I would have exhausted the work. Because the work is representing something it is possible to drain the work of its impact and sensation. If I don’t go to see it for a long time when I return I may experience some emotion, but this will be because of an ill-remembered aspect of the work such as its size or a new gallery position, not because of anything ‘in’ the work itself.

As such the non-Modernist works have a transitory novelty, the better ones involving you in some intellectual game, but in their confrontational nature they lack beauty. The very nature of works which usually involve some participatory role for the viewer stops us from enjoying the work: as Fried wrote, ‘For Judd, as for literalist sensibility generally, all that matters is whether or not a given work is able to elicit and sustain interest’.

I

am not for one minute suggesting that all non-Modernist works should

be consigned to some scrapheap, as I said above the Whiteread work

did give me satisfaction, to have ‘worked it out’ and then,

having done so, to try to imagine the lives of those captured in the

remnants. But the work cannot take me further in Plato’s terms

(although slightly out of context), ‘to more worthy beauties,

to wisdom and virtue’.

I

am not for one minute suggesting that all non-Modernist works should

be consigned to some scrapheap, as I said above the Whiteread work

did give me satisfaction, to have ‘worked it out’ and then,

having done so, to try to imagine the lives of those captured in the

remnants. But the work cannot take me further in Plato’s terms

(although slightly out of context), ‘to more worthy beauties,

to wisdom and virtue’.

I would like to believe Robert Storr when he says that painting is not dead, but has fallen into disuse or misuse. Aside from the political or social upheavals that may have given rise to the non-Modernist movements I think one problem that Fried and Greenberg had realised with the theory of Modernism was the end game, were Olitski and Newman as far as they could go (and who else was taking on the mantle), or as Burgin puts it, were we at, ‘ 'the terminal point of [a] historical trajectory' . I think Fried tried to progress Modernism by the inclusion of the sculptures of Caro but in so doing fractured the Modernist theory.

Other art-historical theories draw back from aesthetic engagement with the work, charging that with being unscientific: the deep empirical analysis of the work probably precludes an aesthetic appreciation anyway.

Let us be clear however, non-Modernist art has not moved us forward, theatrical art was already a well trodden path, by the Futurists, the Expressionists, the Dadaists, and the Surrealists, in some ways post-Modern art is Pre-Modern art. At least now the avenues have all been explored: when we reach a problem often the best step is to retrace our steps to where we began and begin again.

All material on danploy.com is the copyright of danploy.com (2004-2024) unless otherwise acknowledged.