.jpg)

In 2007 I achieved a Masters degree in Art History from the Open University. It was the completion of eight years of study starting with the Introduction to Humanities course, A103, through A216, A354, A316, A424, AA318, A840, A841 and finally A847.

My motivation for the starting the course was twofold, to learn more about the history of painting and to understand why it is that certain paintings I find more pleasurable than others. I certainly learnt much about the former but I also learnt that the latter is now more the domain of philosophy departments than art history departments.

I have also included my essay on the enigmatic painting, 'The Mystic Marriage of Saint Catherine' by Barna da Siena, which was my project for the Open University A424 course on Religious Art in Italy, 1300-1500.

A Tension between Form and Narrative: Rachel Whiteread’s ‘beds’

You can read my Masters dissertation here, and here is the abstract:

In this dissertation, I consider the ‘bed’ works of the British sculptor, Rachel Whiteread. These works were completed between 1988 and 1992, and comprise the casts of the spaces underneath or inside beds and mattresses. In particular I wish to examine what Keith Patrick calls, ‘the tension between the physical presence of the sculpture-as-object and the history which predates it’. In Chapter 1 I will analyse the critical reaction to these works, and in particular note the constant references to the formal nature of the works whilst also discussing the lack of critical engagement with this aspect of her work and evaluating the various and varied critical viewpoints that are explored. In Chapter 2 I will look at the anthropomorphic nature of her work and I will argue that it is this facet of her work that leads to the viewer engaging with the work as a more formal object. I will compare Whiteread’s work with the work of two contemporary female artists, Emin and Lucas, and discuss why these works are perhaps more ‘literal’. To aid in this analyse I will draw on the concepts of ‘instantaneousness’ and ‘presence’ as used by Michael Fried whilst also looking at the Minimalists’ objection to anthropomorphism in an artwork. In Chapter 3 I will look at the reaction between the viewer and the artwork in the gallery space. Again I will argue that Whiteread’s choice of placement and orientation of the work gives her work a more formal aspect. Here I will draw on Michael Fried’s concept of ‘theatre’ whilst also using the idea of ‘horizontality’ and ‘verticality’ as outlined by Rosalind Krauss and Hal Foster. Lastly I will conclude the dissertation, where I will agree with Patrick that a tension does indeed exist and Whiteread’s bed works do indeed have both elements of form and narrative but the position of the fulcrum of the tension is dependent on the viewer-perceived anthropomorphism of the work and also its orientation in the gallery space.

So how did I become interested in Art History?

I was on holiday in Portobello, just outside of Edinburgh,

(a strangely faded seaside resort with a beauty of its own: there

are some pictures here: Portobello

Photographs). I had

walked along the seafront to the city centre before it started raining.

Looking for somewhere outside of the rain I noticed the art gallery

had a special exhibition of William Gillies, a Scottish

watercolourist, (not that I knew of him then). However I had always

enjoyed wandering around art galleries so in I went.

I

did what I think most people do in art galleries, wandering around

fairly aimlessly, stopping slightly longer at works I liked, ignoring

those I didn’t. A young curator was taking around a group

of school children, no more than five or six years old. Normally

I would have immediately gone into another room of the gallery

but I decided to listen to the curator who got the children to

sit in front of one particular painting, a head and shoulders portrait

of what looked like a well-to-do lady.

I

did what I think most people do in art galleries, wandering around

fairly aimlessly, stopping slightly longer at works I liked, ignoring

those I didn’t. A young curator was taking around a group

of school children, no more than five or six years old. Normally

I would have immediately gone into another room of the gallery

but I decided to listen to the curator who got the children to

sit in front of one particular painting, a head and shoulders portrait

of what looked like a well-to-do lady.

When the children were settled the curator asked for them to look at the painting

for a few minutes. She then asked if they liked the painting. The girls did,

the boys less so, I was with the boys. She then asked why they liked it. After

a pause one of the girls said it was because she was so pretty. Then the curator

asked “Did the painter like this lady?” I had never asked a question

of myself like that before. I was started to think about a painting that I

would have walked straight past before: and thinking for myself about it, not

just reading the information off the plaque by the side of picture. A boy said, “Yes,

because the painter has painted her prettily with pretty clothes and jewellery”.

I don’t think I could have answered the question.

The children and curator moved on to a much older painting of a classroom of

unruly children with a disinterested schoolteacher asleep. The children liked

this painting, (so did I): there was a lot going on. The curator pressed, “Who

or what is looking at this, can you see something in the painting”. There

was, an owl, (a child spotted it before me). “Why is an owl looking on?” Of

course wisdom, I did know that, (my hand was up first), there was a message

in this painting, it wasn’t just a painting of a classroom. But then

why would a painter just paint that subject? Why does any painter paint any

subject? Feeling guilty of looking like some hormonally challenged backward

child I decided to stop following the class around, but as I left the gallery

I decided I had to learn more about painting and on my return home started

to look for courses. As an engineer I had rarely read anything that didn’t

have equations in it (that art is for sissies had been ingrained in me), so

I enrolled on an introductory humanities course (A103) at the Open University

in the UK, a home study university. Eight years later I found myself submitting my dissertation for a Masters degree in Art History.

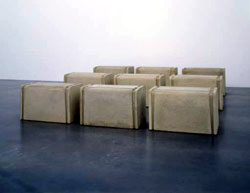

Rachel

Whiteread's Nine Tables: Formal Space, Feminist Space and the Space

In-between? This is my second year

Master's project for the Open University (A841). 'In this essay I will

consider a sculpture, Untitled, (Nine Tables), (1998,

Fig.1 and Fig.2), by the British artist,

Rachel Whiteread. This work is a concrete cast of nine second-hand tables, or

more accurately, a cast of the space underneath the tables, what has been called

the negative space. As such her casts are

imprinted with the residue from the people that inhabited these spaces and her

work has been interpreted as alluding to loss and memory; ‘as metaphors

for the human body or as spaces emptied of their occupants who, in their absence,

nonetheless leave a trace or an imprint of their missing presence’.

Casts raise questions about the ‘displacement of past into present, the

tracing of absence’ and sculpture

also questions the relationship between the viewer and the object.....'

Rachel

Whiteread's Nine Tables: Formal Space, Feminist Space and the Space

In-between? This is my second year

Master's project for the Open University (A841). 'In this essay I will

consider a sculpture, Untitled, (Nine Tables), (1998,

Fig.1 and Fig.2), by the British artist,

Rachel Whiteread. This work is a concrete cast of nine second-hand tables, or

more accurately, a cast of the space underneath the tables, what has been called

the negative space. As such her casts are

imprinted with the residue from the people that inhabited these spaces and her

work has been interpreted as alluding to loss and memory; ‘as metaphors

for the human body or as spaces emptied of their occupants who, in their absence,

nonetheless leave a trace or an imprint of their missing presence’.

Casts raise questions about the ‘displacement of past into present, the

tracing of absence’ and sculpture

also questions the relationship between the viewer and the object.....'

I used to be a quite regular

visitor to the Tate Modern Gallery in London, something now curtailed

by my move to Singapore. Most of the visits were opportunistic: usually

I was in London for another reason and I did not expressly visit

to see any particular special exhibition. As such I tended to wander

without much purpose, happening upon old friends (“Oh good

you are still here, how are you? I have missed you: Are they taking

care of you?”), and if lucky discovering a new hanging by a

favourite artist or one I had previously missed. The works that engender

this warmth and familiarity, and also produce the ‘Wow’ factor

are produced by a relatively few number of artists and in this essay

I will examine why it is only they that give me this experience.

I used to be a quite regular

visitor to the Tate Modern Gallery in London, something now curtailed

by my move to Singapore. Most of the visits were opportunistic: usually

I was in London for another reason and I did not expressly visit

to see any particular special exhibition. As such I tended to wander

without much purpose, happening upon old friends (“Oh good

you are still here, how are you? I have missed you: Are they taking

care of you?”), and if lucky discovering a new hanging by a

favourite artist or one I had previously missed. The works that engender

this warmth and familiarity, and also produce the ‘Wow’ factor

are produced by a relatively few number of artists and in this essay

I will examine why it is only they that give me this experience.

This essay will consider two

recent texts on Jackson Pollock, by Sue Taylor, (2003), and Suzette

Doyon-Bernard (1997). The latter article offers us a detailed iconographic

analysis of one of his earlier works, Male and Female (1942), comparing

the various motifs and symbols with Peruvian Chavin art, and in particular

the Tello Obelisk. The former article analyzes the motifs and symbols

in Pollock’s, Stenographic Figure, (1942).

This essay will consider two

recent texts on Jackson Pollock, by Sue Taylor, (2003), and Suzette

Doyon-Bernard (1997). The latter article offers us a detailed iconographic

analysis of one of his earlier works, Male and Female (1942), comparing

the various motifs and symbols with Peruvian Chavin art, and in particular

the Tello Obelisk. The former article analyzes the motifs and symbols

in Pollock’s, Stenographic Figure, (1942).

Wölfflin’s principles of art history contrast five different concepts of art: Linear and Painterly; Plane and Recession; Closed and open form; Multiplicity and Unity; Clearness and Unclearness. I will extend Wölfflin’s comparative techniques, and his concepts of the imitative and decorative, outside of the timeframes he largely restricts himself to (Classic, sixteenth century and Baroque, seventeenth century), and show how his formalist concepts are equally relevant today.

This essay was originally written for A316 and was in answer to the question, Demonstrate the significance of the concepts of 'expression' and 'decoration' in the work of French and German artists active between c.1890 and c.1914.

The

unusual iconography in ‘The Mystical Marriage of Saint Catherine, ’Barna

da Siena, c.1340. This essay discusses some of the

unique representations in Barna da Siena’s painting of the Mystical

Marriage of Saint Catherine. In the two centuries of interest

for the a424 course (1300-1500) there are several portrayals of the

Mystical Marriage but Barna’s painting shows a number of unique

portrayals, for example in the adult figure of Christ in the Mystic

Marriage, the portrayal of Saint Margaret and Saint Michael and the

enclosure of the smaller scene of the Virgin Mary, Christ Child and

Saint Anne. This essay will try to offer reasons why these particular

portrayals were chosen and discuss how they might relate to the patronage

and contentious approbation of the painting.

The

unusual iconography in ‘The Mystical Marriage of Saint Catherine, ’Barna

da Siena, c.1340. This essay discusses some of the

unique representations in Barna da Siena’s painting of the Mystical

Marriage of Saint Catherine. In the two centuries of interest

for the a424 course (1300-1500) there are several portrayals of the

Mystical Marriage but Barna’s painting shows a number of unique

portrayals, for example in the adult figure of Christ in the Mystic

Marriage, the portrayal of Saint Margaret and Saint Michael and the

enclosure of the smaller scene of the Virgin Mary, Christ Child and

Saint Anne. This essay will try to offer reasons why these particular

portrayals were chosen and discuss how they might relate to the patronage

and contentious approbation of the painting.

All material on danploy.com is the copyright of danploy.com (2004-2024) unless otherwise acknowledged.