.jpg)

The unusual iconography in

‘The Mystical Marriage of Saint Catherine’

Barna da Siena, c.1340

Contents

Illustrations

Acknowledgements

Introduction

The Legend of Saint Catherine of Alexandria

The Life of Saint Catherine

The Mystic Marriage of Saint Catherine

Approbation

Patronage

Formal Analysis

Overview

Saint Catherine

Adult Christ

Saint Anne and Saint Mary with Christ child

Left ‘Predella’

Centre ‘Predella’

Right Predella

Conclusions

Notes

Bibliography

Primary Sources

Secondary Sources

Illustrations

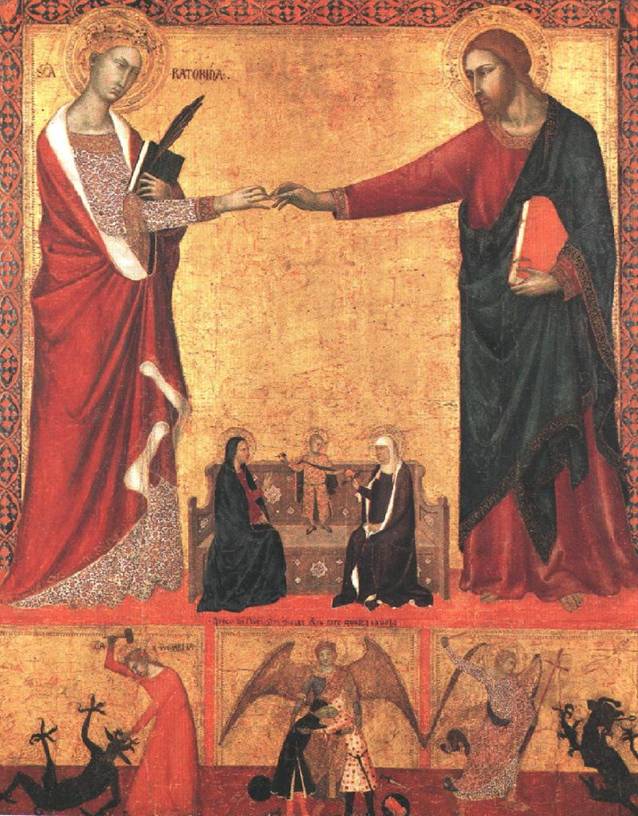

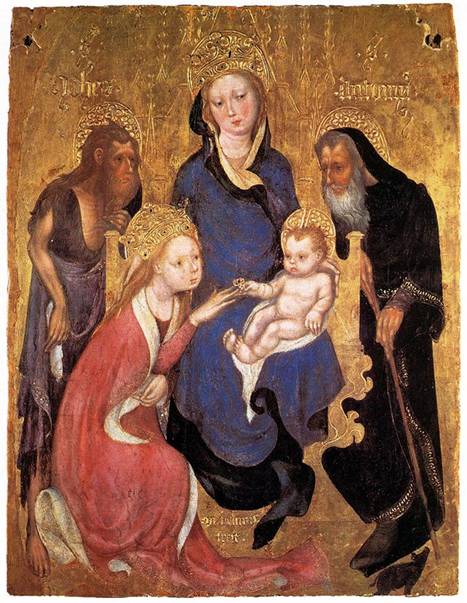

Figure 1 Mystic Marriage of Saint Catherine, Barna da Siena, c1340, Patron: Arico de Neri Arighetti, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, USA, Tempera on wooden panel, 134.8cm x 107.1cm (Image obtained from Boston MFA website)

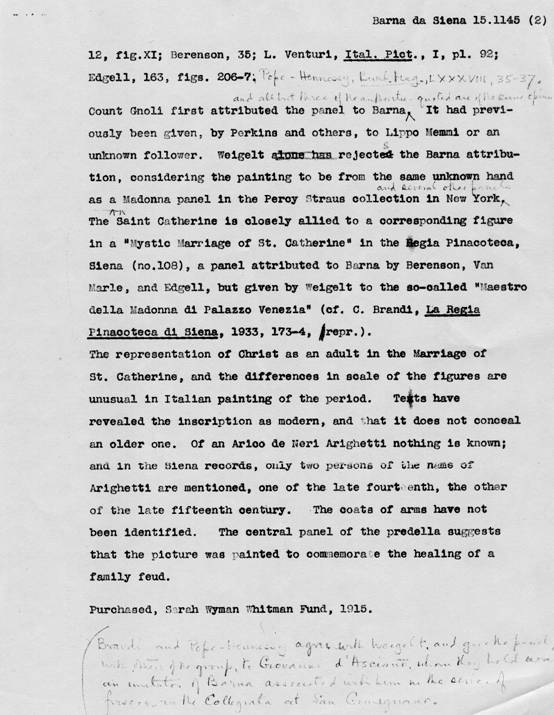

Figure 2 Anonymous article from the Research department of Boston Fine Arts Museum

Figure 3 Map of Siena and San Vincenzo(from MapQuest web-site)

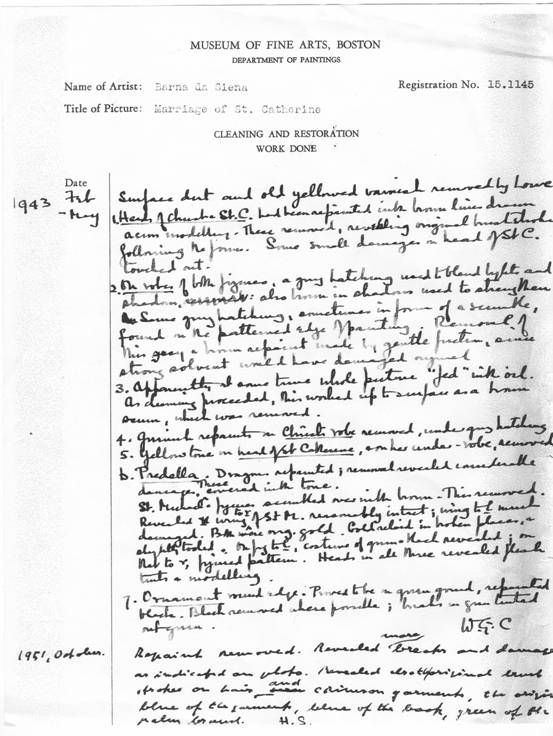

Figure 4 Boston Museum of Fine Arts, Department of Painting, Cleaning and Restoration work done on ‘Mystic Marriage of Saint Catherine’, Barna da Siena, c.1340.

Figure 5 The Mystical Marriage of Saint Catherine attended by SS Joseph, John the Baptist, Peter, Paul and Sebastian. Filippino Lippi, 1501, San Domenico, Bologna. National Gallery London UK

Figure 6 The Mystic Marriage of Saint Catherine, St John the Baptist, St Antony Abbot, Michelino da Besozza,c. 1420, Pinacoteca Nazionale, Siena

Figure 7 Mystic Marriage of Saint Catherine, Giovanni del Biondo, 1379, Tempera and gold on panel, Allentown Art Museum. (Image obtained from Allentown Art Museum website).

Figure 8 Virgin Child and Saint Anne, Francesco Traini, Princeton University Art Museum.

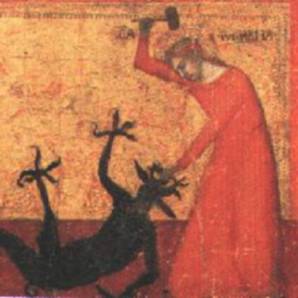

Figure 9 Mystic Marriage of Saint Catherine, Barna da Siena, c1340, (Detail of left predella), Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, USA

Figure 10 Mystic Marriage of Saint Catherine, Barna da Siena, c1340, (Detail of centre predella), Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, USA

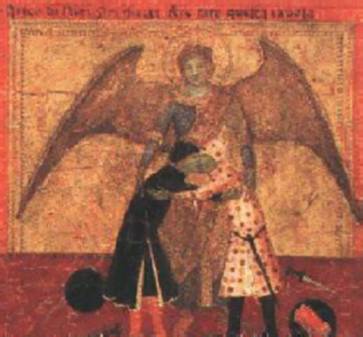

Figure 11 Mystic Marriage of Saint Catherine, Barna da Siena, c1340, (Detail of right predella), Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, USA

Figure 12 Boston Fine Arts Museum

Figure 1 Mystic Marriage of Saint Catherine, Barna da Siena, c1340, Patron: Arico de Neri Arighetti , Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, USA, Tempera on wooden panel, 134.8cm x 107.1cm (Image obtained from Boston MFA website [Note 1] )

Acknowledgements

I would like the thank the considerable help given by the curators and research staff at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts and in particular their research assistant, Kathleen Drea. Additionally I would like to thank Carolyn Muir at the Hong Kong Museum of Art for pointing me in the right direction with my research.

Introduction

The essay discusses some of the unique representations in Barna da Siena’s painting of the Mystical Marriage of Saint Catherine. In the two centuries of interest for the a424 course (1300-1500) there are several portrayals of the Mystical Marriage but Barna’s painting shows a number of unique portrayals, for example in the adult figure of Christ in the Mystic Marriage, the portrayal of Saint Margaret and Saint Michael and the enclosure of the smaller scene of the Virgin Mary, Christ Child and Saint Anne. This essay will try to offer reasons why these particular portrayals were chosen and discuss how they might relate to the patronage and contentious approbation of the painting.

The Legend of Saint Catherine of Alexandria

The Life of Saint Catherine

The first literary account of Saint Catherine appears in the ninth century Menologium Basilianum, a collection of legends compiled for Emperor Basil II who died in 886 [Note 2 ], and is supposedly rooted in the story of Hypatia who was as equally renowned for her learning as Saint Catherine, and who died in 415 [Note 3]. In this book her story is recounted (she is called Aikaterina in the text) [Note 4 ]:

‘The martyr Aikaterina was the daughter of a rich and noble prince of Alexandria. She was very beautiful, and being at the same time highly talented, she devoted herself to Greek literature as well as to the study of the languages of all nations, and so she became wise and learned. And it happened that the Greeks held a festival in honour of their idols; and seeing the slaughter of animals, she was so greatly moved that she went to the King Maximinus and expostulated with him in these words: 'Why hast thou left the living God to worship lifeless idols?' But the Emperor caused her to be thrown into prison, and to be punished severely. He then ordered fifty orators to be brought, and bade them to reason with Aikaterina, and confute her, threatening to burn them all if they should fail to overpower her. The orators, however, when they saw themselves vanquished, received baptism, and were burnt forthwith, while she was beheaded.’

A later Greek text by Simeon Metaphrastes and another later again by Athanasios became the prototypes for all later versions of the story. It was probably at the beginning of the fourteenth century that a new chapter was added which told of her betrothal to Christ.

The Mystic Marriage of Saint Catherine

The first account of Saint Catherine of Alexandria’s mystic marriage is in a story known to exist in 1337 [Note 5]and probably before (the story was already portrayed in 1345 [Note 6]). In the story it was a statue of the Virgin and Child given to her by her hermit mentor, that the child Christ turned towards her to place a ring on her finger. There was three hundred years between the death of Christ and when Saint Catherine lived, but the Christ child is usually portrayed in art to further signify it is a spiritual marriage and not a carnal one (Catherine was a virgin). Further the iconology draws on the medieval conception of the bride of Christ representing the soul, i.e. the mystic marriage represents the marriage of the soul to Christ [Note 7 ] .

Prior to this story there is no literary reference to the mystic marriage of Saint Catherine of Alexandria being to the adult Christ. Indeed the first account of a mystic marriage to an adult Christ is to Catherine of Siena and this did not occur until the problematically dated, but certainly late fourteenth century, Nova legenda (‘iuvenis pulcherrimus quasi viginti quinque annorum’) [Note 8].

The inspiration for this expansion of the story could have come from a text, the Miracoli, telling the story of the mystic marriage of Catherine of Siena as translated here by Millard Meiss [Note 9]:

‘One day she suddenly went out of the house and out of Siena by the Porta di Sant’ Ansano to a region where she thought there were certain dells and caves almost hidden from the eyes of men; there she entered into one, and finding herself in a place where she could neither been seen nor heard, she kneeled on the ground, and in a transport of overwhelming love called the mother of Christ, and with a childlike simplicity asked her to give to her in marriage her son Jesus; and praying thus she felt herself raised somewhat from the ground into the air, and presently there appeared to her the Virgin Mary with her son in her arms, and giving the young girl a ring he took her as his spouse and then suddenly disappeared; and she found herself set back on earth and she returned to Siena and to her home.’

It is estimated that this event in Catherine of Siena’s life would have occurred between 1354 and 1362 but the marriage at this point is still to a child Christ. Raymond of Capua expands upon this story in his Legenda maior, written after her death between 1385 and 1395, and in this version for the first time weds the saint to the adult Christ [Note 10 ].

The first written account of the mystic marriage of Saint Catherine of Alexandria to an adult Christ is by Jean Mielot [Note 11], (at the request of Philip the Good of Burgundy, mid fifteenth century). It was in a vision that she shared with her mother, Queen Sabinella that she underwent the mystic marriage to Christ, although only after she was baptized. It is described thus in the latter story [Note 12],

‘Once, when St. Catharine was praying fervently in her chamber, Jesus Christ, the King of Glory, appeared before her, clad in fine apparel and accompanied by a great throng of angels and saints. As testimony that he accepted St. Catharine for his bride he placed a real ring upon her finger and promised to perform great things for her if she would remain faithful in her love, and when our Lord Jesus Christ had disappeared she knew at once that vision was to be understood in a spiritual sense. She was completely converted to a great divine love and reverent tenderness toward Jesus Christ, her spouse. From this time forth she often received great tasks of consolation from him, and in order that she might take comfort in him more fully she consecrated all her time and all her study and meditations to prayer and the reading and contemplation of Holy Scripture. As formerly she had studied most zealously and had become learned in vast numbers of volumes of profane science, now, after her conversion she applied herself to the books of Holy Scripture, especially to the writings of the Evangelists, giving to these her attention above all else. She said to herself: 'Alas, sinner that I am, how long have I wasted my time in the darkness of profane books! Oh Catharine, here is the Gospel of thy spouse. Put all thy heart upon its teachings as faithfully, and constantly as thou canst in order that thou mayest attain the light of truth.'

Clearly the Boston Marriage painting predates all of these texts: even accepting the later date of Vasari, Barna was dead by 1381 [Note 13 ]. Accepting the date of the Barna Mystic Marriage there appears to be no contemporary written text now existing that tells of Catherine of Alexandria’s marriage to an adult Christ.

However it is not impossible that Barna chose to portray an adult Christ without a literary precedent, given his altered versions of the predella paintings, as we shall later see, drawing on the medieval iconography of Saint Catherine representing the marriage of the soul to Christ, uniting human and divine.

Approbation

As John White writes, ‘Barna is among the ghostly figures dwelling on the fringes of recorded history’ [Note 14].

When Boston first acquired the Mystic Marriage they accepted its attribution as being by Lippo Memmi and it was Count Gnoli who first suggested the attribution to Barna [Note 15 ], a view which was backed up by Doctor van Marle [Note 16]and Frederic F. Sherman [Note 17 ]. Indeed Bernard Berenson attributes some seventeen works to Barna including the Boston Mystic Marriage [Note 18 ]. Weigelt (1931), whilst accepting the existence of Barna, assigned the painting to one of his followers, christening him the Master of the Straus Madonna [Note 19]whilst Millard Meiss also attributes the painting to one of Barna’s associates [Note 20 ]. It has been suggested that Barna may have been a pupil of Lippo Memmi [Note 21]or possibly have been a pupil of Memmo di Filipuccio (as was possibly Simone Martini, who married his daughter), the father of Lippo Memmi. Vasari tells us that Giovanni d’Asciano assisted Barna in his frescos at S.Gimignano, and it is this artist that John Pope Henessey thinks painted the Boston Marriage. However d’Asciano is known to have only been active in the latter two decades of the fourteenth century which surely places it too late through consideration of the paintings style. Ghiberti’s Commentarii associated him with the frescos in the Collegiata at S.Gimignano [Note 22], the works most frequently attributed to him.

Erling Skaug has analysed the punches used in the painting [Note 23 ]:

‘One particular punch appears in most of these paintings, a large triangular leaf with a short stem, which although typologically derived from Memmi (S.Gimignano frescos of 1317) and Martini (Orvieto polyptych c.1320), may have been one of Barna’s favourite motifs.’

Frank Jewett Mather Jr. suggests [Note 24 ]that Barna’s technique is a criticism of the Sienese school as he ‘silently insists that one may be decorative without too much artifice and dramatic without overtaxing the stage carpenter.’ Barna’s style does appear to be a unique mix of the Florentine rigidity and Sienese warmth which I feel adds further weight, as discussed in the chapter on patronage, to Barna having been outside of the Sienese school and therefore why there are no records of him having worked in Siena.

For the purposes of this essay the attribution is important only in any precedence it can give to the reason for the unusual choice of the portrayals. Certainly we can trace the style of Barna from Duccio, (c.1255-1319), to Simone Martini (c.1280-1344), through to Lippo Memmi (c.1285-1361). Barna achieves a unique emotional power in his work and is prepared, unlike his contemporary artists, to sacrifice the accuracy of the portrayal to heighten the emotional power of the work. I think the key to the choice of his unusual portrayals in this work is to achieve a complete emotional power for the painting as a whole through symmetry. This harmony of picture content through the equal and opposite poses of the adult Christ and Saint Catherine and the Saints Margaret and Michael, achieved through distortion of their traditional stories, reflects perfectly the purpose of the painting, the harmony achieved between two previously warring families. Whoever we attribute this painting to, it does not seem to be any of the above suggested alternative artists as none of them show such radical stylistic liberties in their known works. Millard Meiss describes Barna [Note 25 ]as, ‘by far the most gifted painter active in Siena around the middle of the century’ and points to the San Gimignano frescoes and the iconography of the Way to Calvary as ‘unprecedented in Italian painting’. Here again a traditional story is manipulated to create a tension appropriate to the scene.

A number of conflicting pieces of evidence hinder the dating of the work. Meiss suggests that the portrayal of an adult Christ only appears in 1350 and for the third quarter of the century [Note 26]whilst Boston Museum attributes the work to circa 1340. Vasari writes that Barna ‘died young’ when falling from scaffolding during the (a generally accepted attribution) painting of his S.Gimignano frescos in 1381, which if true would challenge the dating of the Mystic Marriage [Note 27]. However Vasari contradicts himself by saying Barna was the master of Luca di Tommè who was already a mature master in 1355 [Note 28]. One further factor to the dating of this work is the severe outbreak of the plague in Siena in 1348 should Barna have been working there (it is estimated over half of the population died).

Patronage

The patronage of the painting seems to be clear as written across the top of the centre predella is ‘Arico de Neri Arighetti fece fare questa tavola’, (Arico de Neri Arighetti had this panel made). However there are still some doubts arising from this. Firstly was the lack of any documentary evidence as to Arighetti: an anonymous text found in the research archives of the Boston Fine Arts Museum, (see Figure 2), states that two people with the name Arighetti can be found in the Sienese records, one late fourteenth century and the other late fifteenth century. Clearly only the former would be of interest but the article does not mention anything more regarding where this information comes from. One thing is clear from the painting, and that is the wealth of the patron, because of the extensive use of gold and silver gilt in the painting.

Figure 2 Anonymous article from the Research department of Boston Fine Arts Museum

However Christina de Benedictus notes that Neri Arighetti is listed among the merchants at San Vicenzo, (see Figure 3 for the proximity of San Vicenzo and Siena), in 1346 [Note 29 ], evidence that is also supported by De Castris [Note 30]. Vicenza was under the control of the Scaligeri of Verona from 1311 until 1387 [Note 31]a courtly culture marked by ‘an interest in secular, chivalric values’ [Note 32]: entirely appropriate to the subject of Barna’s painting. A coat of arms appears to be present in the top left and right of the paintings border but unfortunately these are now unrecognisable.

Secondly the author of the above anonymous article (Figure 2, ‘texts reveal the inscription as modern’), and also Lois Drewer casts doubt on the inscription, suggesting it was a later addition [Note 33]although this is currently disputed by the Boston Museum (‘there is no reason to believe this inscription is a later addition, as has frequently been claimed’ [Note 34 ]).

Figure 3 Map of Siena and San Vincenzo(from MapQuest web-site [Note 35 ])

The painting appears to have been commissioned to celebrate the ending of feud between two warring families. The chapter on the centre predella describes this in more detail.

Formal Analysis

Overview

The painting measures 134.8cm x 107.1cm excluding the frame which makes the figures of Christ and Saint Catherine appear approximately half size, and the medium is tempera on a vertical grain wooden panel, approximately 2.5cm thick and backed with wax resin. The present frame is a more modern addition. The painting is owned by the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, USA, their reference number is 15:1145. It has only been cleaned and restored twice by the Boston Museum, in 1943 and 1951, when some scumble was removed to reveal original brushstrokes on the heads and robes of Saint Catherine and the adult Christ and on the figure of Saint Michael. The report on the cleaning is shown in Figure 4.

Some cracking is apparent which is caused by the gesso under-layer covering an earlier image on the panel, an indication also that the painting may have been done in a more provincial location where new properly prepared panels may not have been so available.

The painting is bordered with a green and blue decoration that has now darkened.

Figure 4 Boston Museum of Fine Arts, Department of Painting, Cleaning and Restoration work done on ‘Mystic Marriage of Saint Catherine’, Barna da Siena, c.1340.

The painting is approximately divided into an upper three quarters where portrayed on the left is the figure of Saint Catherine, on the right the adult Christ, and at the bottom centre the seated figures of Saint Anne and the Virgin Mary with the standing figure of the Christ Child. Below this, similar to the predella of an altarpiece are three smaller paintings united by a red frame and with a common background. The left of these shows Saint Margaret slaying a demon, the right shows Saint Michael doing the same and the centre shows the reconciliation of two enemies under the auspices of an angel.

Saint Catherine

Saint Catherine’s lifelong dedication made her, especially to Franciscans and Dominicans, an ideal example of the vita contemplative and therefore an ideal subject for a reflective painting such as this.

The half height figure of Saint Catherine is dressed in an ermine lined red cloak over a highly decorated dress with gilt sgraffito trim on the cuffs and collar, indicative of her royal birth. In her left hand she holds palm of martyrdom and a black book (she is sometimes shown holding a book with the inscription ‘Ego me Christo sponsam tradido’, I have offered myself as a bride to Christ [Note 36], but it also represents her learning), whilst her right hand is extended out to accept the ring from Christ. The figures of Christ and Saint Catherine are distanced, both of their robes extend over the frame border emphasising the distancing, presumably to ensure that the required reading is given to the ‘marriage’ i.e. that of the marriage of an earth bound soul to Christ. Both Christ’s and Saint Catherine’s gaze is towards the ring, emphasising the spiritual union and, symbolically, the new found union between the families. Saint Catherine’s traditional emblem of the spoked wheel is not shown in Barna’s painting, perhaps why she is positively identified by the inscription ‘SCA KATORINA’ around her head. Again the symmetry of the painting would be upset by the inclusion of this identifier.

Adult Christ

The half true-height figure of Christ is wearing a dark blue mantle over a red robe: his right hand is outstretched holding the ring between his thumb and index finger whilst his left hand is clutching a large orange book.

The unusual portrayal here is that of an adult Christ instead of a Christ child. Near contemporary Italian representations of this time include [Note 37 ]:-

-

The Mystical Marriage of Saint Catherine attended by SS Joseph, John the Baptist, Peter, Paul and Sebastian. Filippino Lippi, 1501, San Domenico, Bologna. National Gallery London UK [Note 38](Figure 5).

Figure 5 The Mystical Marriage of Saint Catherine attended by SS Joseph, John the Baptist, Peter, Paul and Sebastian. Filippino Lippi, 1501, San Domenico, Bologna. National Gallery London UK [Note 39 ]

-

The Mystic Marriage of Saint Catherine, St John the Baptist, St Antony Abbot , Michelino da Besozza,c. 1420, Pinacoteca Nazionale, Siena [Note 40 ](Figure 5).

Figure 6 The Mystic Marriage of Saint Catherine, St John the Baptist, St Antony Abbot , Michelino da Besozza,c. 1420, Pinacoteca Nazionale, Siena

-

Marriage of Saint Catherine: Saint Peter and John the Baptist: Saints Gervasius and Protasius , Puccinelli, ( Lucca: Museo di Villa Guinigi, c1350).

-

Mystic Marriage of Saint Catherine , Giovanni del Biondo, 1379, Tempera and gold on panel, Allentown Art Museum (Figure 7).

Figure 7 Mystic Marriage of Saint Catherine, Giovanni del Biondo, 1379, Tempera and gold on panel, Allentown Art Museum. (Image obtained from Allentown Art Museum website [Note 41]).

This representation differs markedly from Barna’s in that the Virgin Mary is shown as an intercessor and the ring is also not shown emphasising the symbolic nature of the marriage. Saint Catherine is also shown slightly lower than the Christ figure and is identified by her spiked wheel. This near contemporary painting I think shows how radical the earlier portrayal of Barna’s is.

Saint Anne and Saint Mary with Christ Child

The representation of Christ child with Mary and Anne emphasises the mortal aspects of Christ.

Seated on a settle that is decorated with geometric patterns in intarsia is, to the left, Christ’s mother Mary and on the right Mary’s mother Saint Anne, wearing the traditional green cloak over a red robe [Note 42 ]. The geometric patterns have attempted (unsuccessfully I think) to be displayed with perspective on the sides of the settle. Between then standing on the settle is the Christ child (whose head is therefore above those of his mother and grandmother), shown wearing a gold brocade tunic: in his right hand he has perched a bird (suggested by Weigeit that the bird is a goldfinch [Note 43], probably through the expected iconology as described by Hall [Note 44]): the breed of bird is not of particular relevance, it is the birds representation of the spiritual ‘winged soul’ that is of relevance, the shift from the material to the spiritual, the putting aside of material differences (possibly the cause of the feud?). His left hand appears to be receiving a red rose from the Saint Anne, although this has been variously (unconvincingly in my view) interpreted as an apple or orange. The orange can be associated with the Virgin Mary and it can allude to the fall of man and his redemption but not in this context (usually in representations of Paradise) [Note 45 ]. The rose is a symbol also usually associated with the Virgin Mary, the ‘rose without thorns’ and also indicates martyrdom [Note 46]. The outstretched pose of the Christ child is echoed in pose of the angel on the centre predella.

This setting of the smaller group enclosed by a larger group representing a different subject has no precedent in Sienese painting. The proximity of the three figures is not without precedence and is known as the S.Anna Metereza of the Anna Selbsdritt [Note 47 ], but here they are seated on each others laps (see Figure 8).

Figure 8 Virgin Child and Saint Anne, Francesco Traini, Princeton University Art Museum.

Left 'Predella'

Figure 9 Mystic Marriage of Saint Catherine, Barna da Siena, c1340, (Detail of left predella), Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, USA

The left predella painting is painted in the Byzantine tradition and shows Saint Margaret in a vermillion cloak, exorcising a demon which she is holding by the horns with her left hand, a representation without parallel in Sienese painting. The Saint is identified by the writing, Sca Magarita and this predella is a correlative to the right predella showing Saint Michael also slaying a demon. As with other aspects of this painting this is a unique representation, usually, she is shown rising out of its belly, or trampling it under her feet or leading it by a cord [Note 48 ]. Margaret is often the companion of Saint Catherine and is the patron saint of those in childbirth. She is not holding her usual attributes of either a cross or palm but she is wearing the crown of martyrdom [Note 49]. The unusual representation, I suggest, is to provide balance and visual harmony to the predella as the action of Margaret is almost exactly echoed in that of Michael and in turn this visual harmony echoes the social harmony between the previously warring families. Saint Margaret’s red cloak is also echoed in the red of Christ’s book diagonally opposite, which together with the tunic of Saint Michael and the dress of Saint Catherine provides a balance and harmony to the painting. This balance in the painting by Barna shows the influence of the more scientific artistic representations of the Florentine school, as opposed to the more sensory representations employed by the Sienese school.

Centre Predella

Figure 10 Mystic Marriage of Saint Catherine, Barna da Siena, c1340, (Detail of centre predella), Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, USA

The centre predella shows an angel dressed in a pink robe reconciling two young noblemen, the one on the left dressed in black and the one on the right in a chequered pink: surrounding them, thrown to the ground, are the swords and weapons of their dispute. It is this panel that discloses the reason for this painting, the reconciliation between two warring factions and I think it is quite reasonable to assume one of those portrayed is the patron, or possibly his son. Lois Drewer has shown [Note 50]considerable evidence for the precedence in this reconciliation scene in then contemporary art and refers to a ‘loveday’ or dies amoris and the ‘kiss of peace’ which seems ton have been customary practice in private peace settlements throughout Europe [Note 51]and appears to me to be a completely plausible explanation for the subject of this central predella.

Right Predella

Figure 11 Mystic Marriage of Saint Catherine, Barna da Siena, c1340, (Detail of right predella), Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, USA

The right predella painting shows the archangel Saint Michael in a white robe and pink mantle lashing a demon with a scourge (a whip), an unusual representation as a sword is traditionally shown and also unusually the demon is not shown being trampled under Saint Michael’s foot. The long staff or cross is also not traditionally associated with Saint Michael, but is a more traditional representation used for an archangel. Saint Michael’s coat of mail is echoed in the diametrically opposite decorative dress.

Conclusions

Barna da Siena’s Mystic Marriage of Saint Catherine is an enigmatic work that despite considerable research still has questions over its approbation, date, patronage and iconology.

In this essay I have tried to bring together the known research on this painting and have attempted to draw some conclusions from the disparate information available.

The choice of the subject matter, the mystic marriage, represents the story of individual salvation, the resolution of the feud between warring families. The left and right predellas show the conquering of the devil, in the fourteenth century believed to be omnipresent and always looking for opportunities to ‘help’ an individual stray from the right path. The centre predella shows the reconciliation, brought about in real life by an intermediary, here shown symbolically by an archangel and as described by Lois Drewer as a loveday. The main subject of the painting shows the result of returning to this righteous path, acceptance by Christ symbolically shown here by the mystic marriage of Saint Catherine, the union of human and Christ. The small group of Saint Anne, the Virgin Mary and the Christ child also emphasise the relationship of Christ with the family and with the earth, emphasising the need and relevance for this reconciliation before death.

The paintings structure itself also symbolises the new found harmony through radical technique and through the liberties taken with the representation of the stories. The picture is carefully balanced, for example in the figure of Christ, shown as an adult and given the same proportions as Saint Catherine. The necessary reverence to the ‘marriage’ is given by the distancing of the figures and by having both figures looking only at the ring. The centre figures of Mary, Anne and the Christ child are also perfectly balanced, the figure of the Christ child echoed in the pose of the archangel in the centre predella. The poses and actions of Saints Margaret and archangel Michael are also chosen for reasons of symmetry and the choice of the colours in their tunics is echoed in the tunic and book held by the adult Christ and Saint Catherine. The whole work has a visual symmetry that would have perfectly reflected the new harmonious relationship between the families.

The radical liberties with the story telling give the painting visual harmony, and to me points to a unique artist. Other radical use of form can be found in contemporary works including the frescos of S.Gimignano that have been convincingly attributed to Barna da Siena, so I am inclined to also attribute this work to him. As to the patronage, I see no reason to doubt the inscription on the painting, especially in light of the records found of an Arighetti in San Vicenzo. Indeed this find appears also to further strengthen the case for Barna, in that the towns association with Verona through the Scaligeri family would also explain the unique style (a combination of Florentine and Sienese schools) displayed in this painting and yet also explain the lack of any literary records of him in Siena.

Notes

-

URL: http://www.mfa.org/artemis/fullrecord.asp?oid=31540&did=500

-

Saint Catherine of Alexandria, Paul Carus, The Open Court, Volume XXI, Chicago 1907. URL: http://www.sacred-texts.com/journals/oc/pc-sca1.htm.

-

Hall’s Dictionary of subjects and symbols in Art, James Hall, p58.

-

As notes [2], The Open Court, Volume XXI, Chicago 1907.

-

This Latin text is published by H.Varnhagen in Zur Geschichte der Legende der Katharina von Alexandrien, Erlangen, 1891, p20ff and quoted by Millard Meiss in his Painting in Florence and Siena after the Black Death, p107.

-

Painting in Florence and Siena after the Black Death, Millard Meiss, p107.

-

Studien aus Kunst und Geschichte, Friedrich Schneider zum 70, Geburtstage, 1906, pp337ff referenced in Painting in Florence and Siena after the Black Death, Millard Meiss, p108, footnote 15.

-

Painting in Florence and Siena after the Black Death, Millard Meiss, p111.

-

Painting in Florence and Siena after the Black Death, Millard Meiss, p111.

-

Barna da Siena, S. Delogue Ventroni, Pisa, 1972.

-

Vie de Ste Catherine d'Alexandrie , Mielot, Jean, 15th cent; texte revu et rapproche du francais moderne par Marius Sepet. Paris : Georges Hurtrel, 1881.

-

As notes [2], The Open Court, Volume XXI, Chicago 1907.

-

The work by Giovanni del Biondo from 1379 (Figure 5), appears to accurately reflect this text.

-

Art and Architecture in Italy 1250-1400, John White, Yale University Press, 1993, p543.

-

Revue de l’art chretien, 1911, p339.

-

Rassegna d’arte senese, Anno XV, p23.

-

Art in America and Elsewhere, Edgell, G.H., Volume XII Number 11, February 1924.

-

Italian Pictures of the Renaissance, A list of the Principal Artists and their Works with an Index of Places Volume 1, Bernard Berenson, Phaidon, 1968, p25.

-

Research notes unattributed, Boston Art Museum , p2.

-

Painting in Florence and Siena after the Black Death, Millard Meiss, Plate 107.

-

Art in America and Elsewhere, Edgell, G.H., Volume XII Number 11, February 1924, p50.

-

The Oxford Dictionary of Art, p43.

-

‘The Saint Anthony Abbot ascribed to Bartolo di Fredi in the National Gallery, London’, Erling Skaug, Institutam Romanum Norvegiae, Arta ad archaelogian et atrium historiam pertinentia, 1975, p150, Footnote [4].

-

A History of Italian Painting, Frank Jewett Mather Jr., Henry Holt and Company, 1923, p88.

-

Painting in Florence and Siena after the Black Death, Millard Meiss, p54.

-

Painting in Florence and Siena after the Black Death, Millard Meiss, p110.

-

It is also suggested that Vasari is wrong and the date should have been 1351 but this seems a convenient explanation.

-

Art in America and Elsewhere, Edgell, G.H., Volume XII Number 11, February 1924, p50.

-

‘Il politia della Passione di Simone Martini e una proposta per Donato’, Antichita viva 15:6 (1976): 11 n40.

-

‘La ‘bottega avignonese’ di Simone’, Simone Martini, Milan, Federico Motta Editore, 2003, 340 n60.

-

The Italian City-Republics, Daniel Waley, Longman, 1988. p208.

-

Siena , Florence and Padua, Art, Society and Religion 1280-1400, Volume I: Interpretive Essays, Yale University Press, 1995, p47.

-

Margaret of Antioch the Demon-slayer, East and West: The Iconography of the Predella of the Boston ‘Mystic Marriage of St. Catherine’ Lois Drewer, GESTA, XXXII/I, 1993, Vol32 No.1 p11-20.

-

Italian Paintings in The Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Laurence B Kanter, Volume I, 13 th-15 th Century, p93.

-

URL :Map

-

Hall’s Dictionary of subjects and symbols in Art, James Hall, p58.

-

Further paintings, painted just outside the period or painted outside of Italy also portray the Christ child. For example:- The Mystic Marriage of St. Catherine , Gerard David, 1505-10, National Gallery London UK . The Mystic Marriage of Saint Catherine , Lorenzo Lotto, 1524, Galleria Nazionale d'Arte Antica, Rome . The Mystic Marriage of Saint Catherine, Lucas Cranach the elder, 1516, Museum of Fine Arts, Budapest . The Mystic Marriage of Saint Catherine, Correggio, 1510-15 National Gallery of Art, Washington . The Mystic Marriage of Saint Catherine, Niccolo Boldrini, c.1540 . The Mystic Marriage of Saint Catherine , Master of Heiligenkreuz, 1380/90 .

-

URL: http://www.philipresheph.com/a424/gallery/piclib/piclib.htm (Note: I have not been able to confirm the location of this painting at the National Gallery).

-

URL: http://www.cartage.org.lb/en/themes/Arts/painting/paintings/pages/M/mystic_m.htm

-

URL: http://www.allentownartmuseum.org/gallery/european/biondo.html

-

Hall’s Dictionary of subjects and symbols in Art, James Hall, p18.

-

Minor Simonesque Masters, Curt Weigeit, Apollo: A Journal of the Arts, Vol 14, 1931, London.

-

Hall’s Dictionary of subjects and symbols in Art, James Hall, p330.

-

Signs and Symbols in Christian Art, George Ferguson, p35.

-

Hall’s Dictionary of subjects and symbols in Art, James Hall, p268.

-

Italian Paintings in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston: 13 th-15 th Century, Lawrence B Kanter, Boston : Northeastern University Press, 1994, p93.

-

Hall’s Dictionary of subjects and symbols in Art, James Hall, p198.

-

Signs and Symbols in Christian Art, George Ferguson, Oxford University Press, 1961, p131.

-

Margaret of Antioch the Demon-slayer, East and West: The Iconography of the Predella of the Boston ‘Mystic Marriage of St. Catherine’ Lois Drewer, GESTA, XXXII/I, 1993, Vol32 No.1 p15.

-

As [47].

Bibliography

Art and Architecture in Italy 150-1400 , John White, Yale University Press, 1993.

Hall’s Dictionary of subjects and symbols in Art , James Hall, The University Press, Revised edition, 1996.

History of Italian Painting , Frank Jewett Mather Jr., Henry Holt and Company, 1923.

Il politia della Passione di Simone Martini e una proposta per Donato , Christina de Benedictus, Antichita viva 15:6 (1976).

Italian Paintings in The Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Volume I, 13 th-15 th Century , Laurence B Kanter, Boston: Northeastern University Press, 1994.

Italian Pictures of the Renaissance (A list of the Principal Artists and their works with an index of places), Central Italian and North Italian schools , Volume I, Bernard Berenson, Phaidon 1968.

Margaret of Antioch the Demon-slayer, East and West: The Iconography of the Predella of the Boston ‘Mystic Marriage of St. Catherine’ , Lois Drewer, GESTA, XXXII/I, 1993, Vol32 No.1

Minor Simonesque Masters , Curt Weigeit, Apollo: A Journal of the Arts, Vol 14, 1931, London.

Painting in Florence and Siena after the Black Death , Millard Meiss, Princeton University Press, 1978.

Painting in Late Medieval and Renaissance Siena (1260-1555) , Diana Norman, Yale University Press, 2003.

Siena , Florence and Padua, Art, Society and Religion 1280-1400, Volume I: Interpretive Essays , Yale University Press, 1995.

Signs and Symbols in Christian Art , George Ferguson, Oxford University Press, 1961.

The Boston “Mystic Marriage of St. Catherine” and five more panels by Barna Senese , Edgell, G.H., Art in America and Elsewhere, Volume XII, Number 11, February 1924.

The Italian City-Republics , Daniel Waley, Longman, 1988.

The Oxford Companion to Christian Art and Architecture , Peter and Linda Murray, Oxford University Press, 1998.

The Oxford Dictionary of Art , edited by Ian Chivers and Harold Osborne, Oxford University Press, 1997.

Figure 12 Boston Fine Arts Museum (Photograph by author)

All material on danploy.com is the copyright of danploy.com (2004-2024) unless otherwise acknowledged.