.jpg)

The Beginning of Formalism

Abstract

Wölfflin’s principles of art history contrast five different concepts of art: Linear and Painterly; Plane and Recession; Closed and open form; Multiplicity and Unity; Clearness and Unclearness. I will extend Wölfflin’s comparative techniques, and his concepts of the imitative and decorative, outside of the timeframes he largely restricts himself to (Classic, sixteenth century and Baroque, seventeenth century), and show how his formalist concepts are equally relevant today. In so doing I will restrict myself to painting.

Introduction

‘The whole progress of the “imitation of nature” is anchored in decorative feeling. Ability only plays a secondary part. While me must not allow our right to pronounce qualitative judgements on the epochs of the past to atrophy, yet it is certainly right that art has always been able to do what it wanted and that it dreaded no theme because “it could not do it”, but that only that was omitted which was not felt to be pictorially interesting. Hence the history of art is not secondarily but absolutely primarily a history of decoration.’

Wölfflin has developed his principles based on the philosophical theories of, amongst others, Kant, Dilthey and Reigl ,, and the formalist aesthetics of Herbart. Dilthey, building on Hegel’s Philosophie des Geistes, believed that the natural sciences, by using external observation and measurement, produce an objective history that is abstracted from a full lived human experience. The history of the humanities, by using the inner self, provides a different history, with a more direct link to our original sense of life. It is this history that Wölfflin seeks to isolate using a formalist technique that analyzes the art work through comparative techniques: to look for the ‘specifically visual’ features of art. This discrimination between ‘general style’ and ‘individual style’ is not meant to mean the latter replaces the former, but to supplement it.

Wölfflin freed the analysis of art from its social and historical perspective: it does not matter if there are one, three or five categories, or if one aspect of the pairing is to be preferred over another, what is important is the way of seeing. It seems relevant to apply an analysis freed from historical constraints to any period of art and to see the relationship between Wölfflin’s formal analysis and that of Modernism’s. Modernism’s preference for the flatness of the picture plane is apparently in contradiction to Wölfflin’s preferred progression from plane to recession, but as I hope to show, it is the technique that is important, the way of seeing. Painting for Wölfflin exteriorized internal emotions: what he attempted to do was to identify and isolate this emotion from the environment the work was created in, and he felt the element that identified this emotion was decoration.

Wölfflin tried to achieve was to isolate that which is specific to the visual arts: later Greenberg would extend this method by highlighting, the ‘declaration of the surface’, the importance of the two dimensionality of painting that discriminates it from sculpture or architecture; and Fried, building on Greenberg’s Modernism, highlighted the uniqueness of painting to be realized instantaneously, discriminating painting from literature or sculpture which only becomes fully apparent over a period of time.

The Imitative and the Decorative

In each of Wölfflin’s five pairs of concepts he tries to isolate the imitative from the decorative whilst also emphasizing his preference for the latter which is sees as a progression from the former. The reason for this preference is, for Wölfflin, expression. The latter is the more expressive art.

Let

us consider Wölfflin’s concepts of ‘plane’ and

recession. The contrast that Wölfflin seeks to demonstrate here

is the development from a simpler foreground/background plane view, to

that of a recessional view where the use of use recession produces multiple

planes. Consider a painting by the French academic painter Adolphe-William

Bouguereau. Although the scene is of a small group of people there is

still a recessional quality to the painting, the figures have no discrete

planes, each figure-distance is also partially occupied by another figure.

This merging of the planes allows the eye to travel through the painting,

also facilitated by the gestures of the figures, and in so doing gives

movement to the painting, a feeling enhanced by the instability of the

upturned pyramid of the foreground figures. Bouguereau wrote,

Let

us consider Wölfflin’s concepts of ‘plane’ and

recession. The contrast that Wölfflin seeks to demonstrate here

is the development from a simpler foreground/background plane view, to

that of a recessional view where the use of use recession produces multiple

planes. Consider a painting by the French academic painter Adolphe-William

Bouguereau. Although the scene is of a small group of people there is

still a recessional quality to the painting, the figures have no discrete

planes, each figure-distance is also partially occupied by another figure.

This merging of the planes allows the eye to travel through the painting,

also facilitated by the gestures of the figures, and in so doing gives

movement to the painting, a feeling enhanced by the instability of the

upturned pyramid of the foreground figures. Bouguereau wrote,

‘One has to seek Beauty and Truth, Sir! As I always say to my pupils, you have to work to the finish. There's only one kind of painting. It is the painting that presents the eye with perfection, the kind of beautiful and impeccable enamel you find in Veronese and Titian .

Bouguereau seeks ‘beauty and truth’, and truth for him is imitation (see Figure 3). Bouguereau’s beauty comes from an idealized imitation of nature, a glossy veneer that prevents expression: there is only technique in the painting, no expression, no tapping of that ‘accumulated strength’ that Matisse believes is inside all artists. As such the work is hollow, a scientific exhibition of technique.

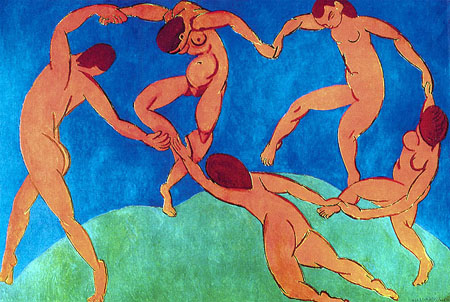

By contrast consider the later Matisse painting shown below. As with Bouguereau’s painting, it is a painting of movement, but by flattening the image by the use of simplified colours and areas of plain colour, the eye is prevented from entering the picture; and Matisse has enclosed his figures in a circle, preventing the eye from moving outside of it. The movement of eye through the Bouguereau painting is analogous to Michael Fried’s ‘theatre’: a recessional image is experienced over time as a narrative and as such it cannot have the ‘instantaneousness’ the Fried believed was essential to a Modernist work. A narrative in a painting routes the art work in its story, not allowing painting to be freed from literature, or as Greenberg puts it, painting becomes the ‘stooge of literature’. Matisse achieves Wölfflin’s ‘movement of colour’, yet does so at the same time as declaring itself a painting. Matisse’s ‘closed’ painting, although of a dynamic event, has a stillness about it.

Matisse’s flattening of form and use of exaggerated colour could be seen as giving the painting a ‘decorative feel’. If we accept this description, why does Matisse prefer this means of expression?

‘ When

the means of expression have become so refined, so attenuated that

their power of expression wears thin, it is necessary to return to

the essential principles which made human language….. Pictures

which have become refinements, subtle gradations, dissolutions without

energy, call for beautiful blues, reds, yellows – matter to stir

the sensual depths in men.’

When

the means of expression have become so refined, so attenuated that

their power of expression wears thin, it is necessary to return to

the essential principles which made human language….. Pictures

which have become refinements, subtle gradations, dissolutions without

energy, call for beautiful blues, reds, yellows – matter to stir

the sensual depths in men.’

To quote Wölfflin, Matisse has ‘relinquished the physically tangible for the sake of mere visual appearance’. The ‘means of expression so refined’ could be applied to Bouguereau painting, paintings whose scientific veneer routes them in the social and historical period they were created in, for by unwittingly excluding the emotion from the painting they are excluded from the ‘history of decoration’. Bouguereau’s paintings of emotion have no emotion and for the first time Wölfflin gives us a technique to be able to understand why.

The quotation from Matisse highlights one important consideration in Wölfflin argument. Wölfflin’s five contrasting concepts are not historical periods: one did not evolve into the other nor is one to be preferred over the other (although Greenberg, who adapted some of Wölfflin’s concepts was more vocal on this point). To use Wölfflin’s own terms, paintings owe more to other pictures than they do to nature. As Matisse writes, his ‘decorative’ style of painting has links with all the past; indeed Matisse can very much be seen as a classical painter, in his style and his subject matter.

‘Composition is the art of arranging in a decorative manner the diverse elements at the painters command to express his feelings.’

Matisse expresses his desire to achieve Wölfflin’s ‘decorative schema’, this is the artist’s choice which is why Wölfflin attributes the history of decoration to the history of art, this is the artist’s free choice.

Conclusion

For

Wölfflin, whilst not ignoring the impact of social and historical

influences on style, underlying art history’s development is

a history of beauty, and it is this undercurrent that defines its ‘progress’ and

style. It is this strong undercurrent that the artist is able to uniquely

tap that defines the history of art.

For

Wölfflin, whilst not ignoring the impact of social and historical

influences on style, underlying art history’s development is

a history of beauty, and it is this undercurrent that defines its ‘progress’ and

style. It is this strong undercurrent that the artist is able to uniquely

tap that defines the history of art.

‘Our senses have an age of development which does not come from the immediate surroundings, but from a moment in civilization….. The arts have a development which comes not only from the individual, but also from an accumulated strength, the civilization which precedes us.’

Wölfflin’s concepts of style and their separation from a traditional evolutionary timeline have important ramifications for art history. Wölfflin largely restricts himself to two historical periods, the Classical and the Baroque, for his analysis, but his ‘way of seeing’ can be applied to all art, especially if ones removes his shackles of the progression he seems to wish to emphasize.

Wölfflin often struggles with certain artworks to place them in one or the other category he prescribed, and it is certainly easy to find works of art that do not follow the ‘progression’ from for example, plane to recession: indeed the Modernist works considered below appear to contradict. This lays Wölfflin out to criticism, from for example, Meyer Schapiro, who points out that Wölfflin conveniently forgets Mannerism and pre-classic art because, according to him, they cannot be fitted into the analysis. I am inclined to feel this is semantics and diminishes the importance of Wölfflin’s formalist technique: Shapiro is a socialist art historian and it is not surprising criticism should come from such quarters.

Wölfflin allows us to appreciate art as an autonomous work of beauty, not just as some reflection of the cultural or political environment in which is was created. It does not matter which is the better method or the more beautiful painting, whether plane is to be preferred over recession: what matters is that, here, for the first time, we have the tools to make a judgement. Abstract art could appear to be ideal for a Wölfflinian analysis for it this art that has tried to remove the signs: Wölfflin ‘seeks to disclose those features of the work that make it more than a mere sign for something that is not present’.

Modernism adopted the formalist analysis of Wölfflin, but it put emphasis on some different areas. First and foremost for Modernism was the autonomy of the artwork, the work was to be freed completely from other art works (sculpture and literature for example), and should emphasize those aspects unique to painting. Modernism took from Wölfflin this autonomy, and with it a set of principles with which to judge a work of art. We may not agree with Wölfflin’s preferences (and Greenberg did not all the time), but for the first time he gave us techniques to allow that judgement.

To finish by highlighting one point: Wölfflin increases the importance of the artist in the creation of the artwork. The artist is not longer constrained by the pervading social and historical circumstances, but has something within to draw on, Matisse’s ‘accumulated strength’. Wölfflin declares the autonomy of the artist: and for this reason Wölfflin prefers the decorative over the imitative, for it is the decorative that comes from within the artist.

Notes

Heinrich Wölfflin, Principles of Art History, pp.231.

Gaiger, In search of the ‘Specifically Visual’ – Wölfflin’s Principles of Art History, pp.5.4

Joan Hart, Reinterpreting Wölfflin. Neo-Kantianism and hermeneutics, pp.294.

Jason Gaiger, The analysis of pictorial style, pp31.

Encyclopedia of Philosphy, pp.211.

Gaiger, In search of the ‘Specifically Visual’ – Wölfflin’s Principles of Art History, pp.5.6

Jason Gaiger, The analysis of pictorial style, pp23.

Jason Gaiger, The analysis of pictorial style, pp25.

Adolphe-William Bouguereau, 1895, URL: http://www.ibiblio.org/wm/paint/auth/bouguereau/

Clement Greenberg, The American Avant Garde, quoted in Art in Theory, pp.563.

Heinrich Wölfflin, Principles of Art History, pp.229.

Henri Matisse, ‘Statements to Teriade’, quoted in Art in Theory, pp.384.

Heinrich Wölfflin, Principles of Art History, pp.229.

Henri Matisse, Notes of a Painter, quoted in Art in Theory, pp.70.

Heinrich Wölfflin, Principles of Art History, pp.229.

Henri Matisse, ‘Statements to Teriade’, quoted in Art in Theory, pp.384.

Jason Gaiger, The analysis of pictorial style, pp25.

Jason Gaiger, The analysis of pictorial style, pp32.

Henri Matisse, ‘Statements to Teriade’, quoted in Art in Theory, pp.384.

Bibliography

Bell , Julian, What is Painting: Representation and Modern Art, (Thames and Hudson, 2004).

Concise Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy , (Routledge, London, 2000)

Fernie, Eric, (selection and commentary), Art History and its Methods, (London: Phaidon Press Limited, 1999).

Gaiger, Jason, In search of the ‘Specifically Visual’ – Wölfflin’s Principles of Art History, A840 Postgraduate Foundation Module in Art History, (The Open University, 2005), pp.5.1-5.25.

Gaiger, Jason, The analysis of pictorial style, (British Journal of Aesthetics, vol.42, 1, 2002), pp. 20-36.

Gombrich, E.H., Norm and Form: The Stylistic Categories of Art History and Their Origins in Renaissance Ideals, Reading 5.1 from A840, The PostGraduate Foundation Module in Art History, (The Open University, 2005), pp.5.1.1-5.1.16.

Greenberg, Clement, The American Avant Garde, (1940, from Art in Theory 1900-2000).

Harrison , Charles and Wood, Paul, Art in Theory 1900-2000, An Anthology of Changing ideas, (Blackwell Publishing, 2003).

Hart, Joan, Reinterpreting Wölfflin. Neo-Kantianism and hermeneutics, (Art Journal, vol.42), pp.292-300.

Matisse, Henri, ‘Notes of a Painter, (1908, from Art in Theory 1900-2000), originally from J.D. Flam, Matisse on Art, 1973.

Matisse, Henri, ‘Statements to Teriade’, (1936, from Art in Theory 1900-2000), originally from J.D. Flam, Matisse on Art, 1973.

Wölfflin, Heinrich, Principles of Art History, (translated by M.D.Hottinger, Dover Publications Inc. , 1950).

Woodfield, Richard, The Essential Gombrich, Selected writings on Art and Culture, (London, Phaidon Press, 1996).

All material on danploy.com is the copyright of danploy.com (2004-2024) unless otherwise acknowledged.